|

|

| Situated between the larger well-constructed stores and the market buildings proper, lies a section of prefabricated

shacks and semi-permanent stalls. This is where the smaller African traders, who deal with manufactured goods,

are sited. The two sectors do to some extent compete directly, however, the smaller traders also specialise in

a variety of smaller items not widely found in the 'Lebanese stores'. You are also more likely to find there those

manufactured goods that have been imported from Guinea. Most of these stallholders are Fula and Mandingo, a few

are Temne. Cloth-traders, tailors and other specialists are to be found here. The tailors are mostly men. Those

situated near the market tend to operate independent enterprises, although a number of tailors also work on the

verandahs of the Lebanese shops. The market buildings proper consist of two open planned iron roofed rectangular buildings, however, the market activities are not necessarily confined there. In the dry season, many traders display their goods outside. The vast majority of table traders inside the buildings sell basic foodstuffs, and are mostly women. There is a lack of specialisation within this general category, and on the same table one may find tomatoes, potatoes, sugar, oranges, rice, eggs, etc. One noticeable exception to this is the fish whose sale is dominated by women. Fresh and dried fish (bonga, Kr.) is regularly brought up from Freetown. The fish sellers are situated near the market butchers. Outside the market buildings there is a clear tendency for sellers of a particular commodity to congregate together. And so one observes clusters of wood sellers, palm oil sellers, sweet potato and potato-leaf sellers, and so on. The basic foodstuffs are mainly sold by women, whilst men dominate the baking and butchering, the sale of medicines, clothes and kola nuts. The size of female market enterprises varies a great deal. Market women may be seen vending with goods only worth thirty pence. However, for many women trading is their full-time profession, and their larger and more permanent stalls may hold goods to the value of a few hundred pounds sterling. (*13) Whilst the market is the visible commercial centre of the town, it is also a social and, in a sense, recreational centre, which provides a meeting place for individuals and groups. It is an obvious focal point for the giving and receiving of news and information. The main marketing activities take place during the hours of daylight, especially between nine and four o'clock. However the market place remains a focal point for social interaction even during the early hours of darkness. Between the Lebanese stores and the main market buildings, sellers of African 'fast foods' such as cakes, fried fish, boiled and roasted corn, groundnuts and, occasionally, roasted meat, gather, under the flickering shadows of kerosene lamps. It is mainly young men who gather at the market place at night, to stand around and gossip, meet their friends, and to listen to the music playing at the nearby bars, but since the fast food sellers are young females there is always the possibility of spending the evening in mixed company! (*14) Specialisation is not entirely absent from the CBD. There is a branch of Barclays Bank on one of the corners of the market centre, and within fifty yards of the market place are two petrol stations, which, including that at the market bar, makes three altogether. Close to the centre there are a number of eating or 'chop' houses, a photographic studio and a 'recording' studio. Within the market itself there is a motorbike taxi rank. The riders operate during the day and well into the evening, carrying messages, or people, in and around town, or frequently, further afield. Two |

|

15 |

|

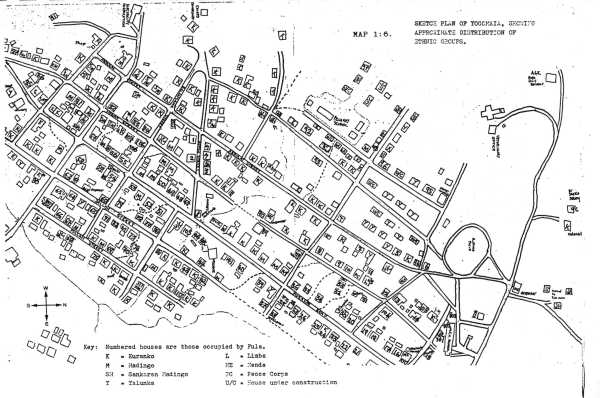

MAP 1:5 |

|

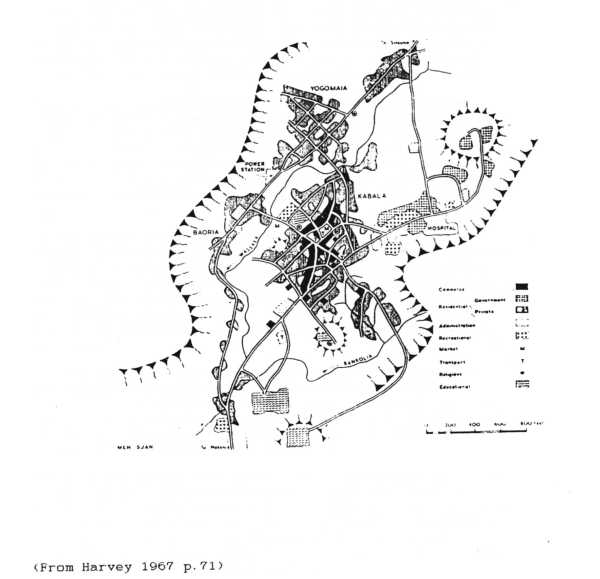

KABALA LAND USE |

|

|

MAP 1:6 |

|

|