|

|

| CHAPTER EIGHT SETTLING DOWN: RESPONSES TO LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENT. |

| Over many decades, strategies for livestock development in Sierra Leone have been couched in terms of settlement schemes and often linked with a desire to encourage mixed farming. Current discussions on livestock development indicate the persistence and pervasiveness of a number of fundamental misconceptions concerning Fula livestock production, and the Fula themselves. |

|

133 |

| i. Introduction: strangers and stereotypes. The typification of pastoralists as inherently "conservative" is widespread. Innumerable studies, especially among the much-maligned East African herders, have repeatedly shown that this pejorative stereotype cannot be supported by fact. (*1) Nonetheless, the myth continues to be retold over and over again, especially in those very echelons whose raison d'être is supposedly to stimulate "development". Certainly, this was my experience in Sierra Leone, where reports and papers frequently projected the image of pastoral conservatism. And whilst it is inevitable that I should come to identify with the people among whom I lived and researched, I was concerned that my own experiences had left me with an entirely different impression and understanding: as I have already observed, I was frequently surprised by the cosmopolitan and adaptive nature of Fula society. There are, I think, two underlying issues here. Firstly, the Fula are seen as "strangers" within Sierra Leone. (See above) Secondly, there is a general misunderstanding concerning the nature of livestock production and the "character" of pastoralists. Generally, attitudes towards Fula husbandry are, I feel, marked by ambivalence and inconsistency. The resultant confusion is exemplified in the following assessment of the livestock industry in Sierra Leone, which appeared in a recent "Sierra Leone Special" edition of West Africa (15 Feb 1988):-"...the cattle industry showed tremendous increases between 1955 and 1970 during which time the national herd almost doubled as a result of effective control measure against the major killers like rinderpest and contagious bovine pleuropneumonia. Notwithstanding this, the complete absence of an integrated approach between livestock and crop and the domination of the cattle industry by a single ethnic group have also contributed to the slow growth and poor performance of the livestock sector as a whole." (p.268; emphasis added.) (*2) Elsewhere, ironically, it is Fula "conservatism", their apparent reluctance to enter the livestock industry, (let alone dominate it!) which is raised as one of the major factors hindering the successful development of the livestock industry. For example:- "On the whole, there appear to have been few changes in customary practices, as described in previous reports, in that there is still an absence of commercial orientation; a reluctance to divulge numbers and allow officials close inspection of herds remains; traditional methods of treatment for sick animals, branding and castration persist; and milking continues at the expense of the calf.". (*3) (Hunting Technical Services 1979 p.47) And more recently, Kamara has written:- "many of the cattlemen have had little outside influences. Among them, the wealth and prestige of a man is measured by the number of cattle at his disposal with little regard to the conditions and quality of his cattle." (1981 p.158) (*4) Yet Holt, the author of an earlier report, comes to a different conclusion altogether. He notes that the cattle herds are maintained as a "source of wealth and social status, as well as for a profit motive", and that the Fula, "perhaps understandably, are reluctant to divulge the size of their 'bank balances' ". (Holt 1973 p.12.) During the course of his research Holt put the following question to Alimamy A.R.Jalloh, then Fula headman of the Koinadugu district (and husband of Haja Aisaitu). "Would it be possible to persuade the Fula to herd for profit instead of status?" Alimamy Jalloh's response is brief but to the point. "The Fula herds for profit instead of status. There is no question of persuasion in this respect." (ibid, appendix 7) |

|

134 |

|

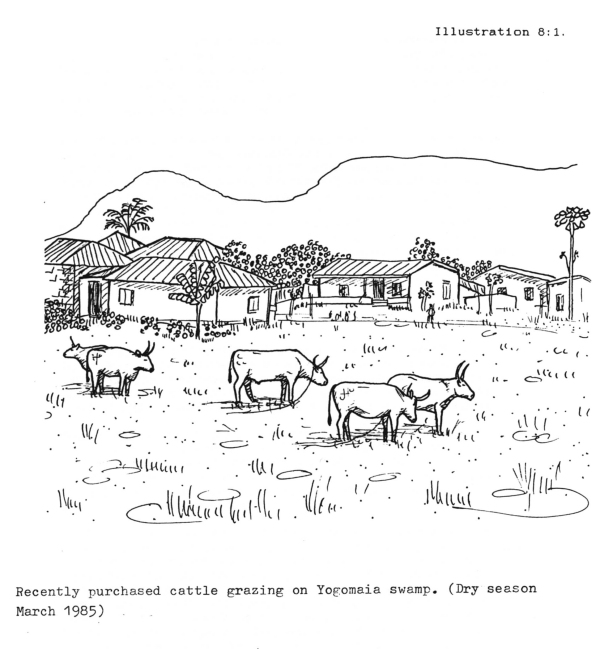

Illustration 8:1 |

|

| In Sierra Leone an indigenously developed meat-marketing system operates, international in its operations, that

has grown in size and complexity without the "assistance" of government or development agencies. (*5)

The system is efficient, flexible and articulate. It also performs the function of integrating the rural and urban

sectors, not just in terms of the expanding market economy, but in the more general sense of human contact and

interaction. The problem for development, if there is to be a problem, is that the Sierra Leonean Government feels that it is missing out and not getting its fair share of these resources. (*6) The problem then is not to be defined in terms of increasing the numbers of stock per se., or in terms of increasing the numbers of cattle that are made available to the market (i.e. the problem of encouraging the conservative pastoralist to part from his cherished status symbols). In other words, the problem for the Government is not one of having to encourage the Fula to enter the modern world of the swinging market economy. On the contrary, the problem is one of controlling that very economy. The difficulties of intervention are such that the market may do a roundabout turn, and the cattle resources be lost to the country altogether. ii. Settlement Schemes. I have already established that the Fula of Sierra Leone are not nomadic, and that their patterns of transhumance are localised. Nonetheless, during the 1950's, the colonial authorities, misinterpreting, perhaps, the immigration of Fula herders from Guinea into Koinadugu District as evidence of pastoral nomadism, (cf. Stenning 1957) put a great deal of effort into setting up a Cattle Owners Settlement Scheme. The scheme aimed to "encourage the settlement of cattle-owners" by persuading them to contain their cattle within reserved grazing areas of approximately one mile each. (*7) The scheme was "ambitious". (Oxby 1985, p.221) The colonial authorities planned for 270 settled and improved areas by the end of 1960. However, by this time of the 116 settlement areas registered only 79 were occupied. (*8) Within a few years the scheme became moribund. A 1962 report, made by the Senior Agricultural Officer based in Kabala, provides the following explanation of the scheme's demise:- "Lack of marketing facilities continued to hamper the scheme and it was not possible to rigidly enforce rules regarding over-grazing. The position was further aggravated by most of the settlements being placed under quarantine restrictions due to an outbreak of bovine plero-pneumonia near Kombile during September".(*9) The reference to "marketing facilities" is, I feel, rather out of place. However, the issues of over-grazing and disease raise the larger question of whether the rigidity of an imposed settlement scheme created more problems for herder, farmer and administrator, than it had been able to solve. Success or failure can be judged with reference to the programme's specified aim: to encourage the settlement of cattle owners within designated herding areas. Clearly, on this basis alone, the scheme was a failure. From the few relevant surviving documents at the Kabala District Office, I learnt of a number of "reasons" which, ostensibly, lay behind the decision to implement the settlement scheme. "Crop damage" (*10), "environmental degradation" (*11) and the |

|

135 |

| "spread of diseases" are frequently mentioned in contemporary correspondence and reports. Over thirty

years later, Reid, District Commissioner for Koinadugu District from 1952-1956, still lists these as the principal

reasons behind the establishment of the scheme. (1988, Personal communication.) Contrary to the opinion of Reid,

who does not appear to have viewed the matter in quite the same way, I think that another major concern was to

secure, for Sierra Leone, the large herds of cattle which had entered the country. The cattle herds represented

an important source of wealth, and the administrators were keen to ensure that their numbers increased. The perceived

mobility of the "nomadic" herders was, consequently, a cause of much concern. (*12) And the colonial

administration looked to settle the herders by providing them with some measure of security; or at least with a

level of security greater than that being provided by their colonial counterparts, across the Guinea border.(*13)

Oxby suggests that one of the major reasons why the Cattle-Owner Scheme failed, was "the difficulty in getting permanent access for the herders to enough suitable land". (ibid.p.225) She argues that the seven year leases were too short to provide herders adequate security of tenure; and the allocated areas of land were too small to support the large herds that many Fula held. (*14) As I have already indicated, in some areas overgrazing became an increasingly serious problem, and it has been suggested that the scheme exacerbated, rather than improved, the relations between herders and landowners. (See below) Behind the manifest problems that arose in many areas where the scheme operated, lay the fundamental issue of land rights. As I have indicated above, the Fula herders, even though many have lived in Sierra Leone for generations, have not established range-land rights. A minority group within larger "indigenous" farming communities, Fula herders are dependent, to a great extent, upon their relationship with local farmers. Land rights are vested in the farming communities. They are the "owners of the land" and, thus, claim priority of access. For example, around Kabala, local people did not consider land to be in critically short supply, yet it was difficult for Fula to obtain productive rights in swamp farmland. By residing permanently in an area, Fula herders are usually able to secure access to land and many herders have developed extensive upland rice farms. In many instances this occurs through intermarriage, or less formal relationships, for example friendship. However, such relationships, although very widespread, remain dyadic and particularised: that is to say, trust and friendship built up in this manner is not generalised to an inter-community or inter-ethnic level. And, as the widespread and bloody violence that occurred between the Yalunka and Fula populations following the 1982 general elections has shown, the local cross-cutting ties, whilst widespread and significant, are also fragile and vulnerable. (See below) Whilst human settlement areas and farming plots can be agreed upon and fixed in the minds of both herding and farming populations, herding areas necessarily remain vague and inevitably contingent upon the particular needs of the farming population. In Sierra Leone, and elsewhere in the sub-humid tropics of West Africa, land-use rights that a farmer has over land he cultivates are seen to be more permanent and inalienable than those that a herder has over the grazing land he uses. (Oxby 1985 p,226) This is the situation today, and I believe that a similar situation existed at the time of the implementation of the Settlement Scheme. Under the scheme land rights were restructured. The creation of reserved farming and herding areas, and the issue of seven year leases were measures taken to formalise the existing ad hoc arrangements between farmer and herder, rather than to replace them altogether. |

|

136 |

| The scheme did not operate long enough to judge whether a successful compromise had been made. Oxby notes that

"crop farmers came to resent the presence of the herders and began to farm so close to the settlement areas

as to deliberately make it impossible to graze without damaging crops". (ibid 225) However, this strategy

was already well established. (*15) I have not come across any evidence to suggest that herder-farmer relations

deteriorated in the areas in which the scheme operated. (*16) On the other hand, it is possible that the scheme

helped to legitimise the presence of the Fula herders in the district. This may have been resented by the indigenous

farming communities. A number of informants recalled how the British had "liked" the Fula and encouraged

them to settle in Sierra Leone. Through the Settlement Scheme, the Fula were brought into direct negotiations with

the colonial authorities. For example, Reid informs me that "Alimamy Jalloh was appointed in 1953 to be vice-president

of all Native Courts in Koinadugu District. This was to ensure that Fulas received a fair deal from these courts

in any dispute involving a Fula and an indegene." (Personal communication, 1988) As the final arbiters of

law and justice, recognition by the colonial authorities of, albeit limited, grazing rights may have strengthened

the position of the Fula vis a vis the indigenous farming communities. However, by 1962, after which the scheme

appears to have gone into decline, the "traditional" relationship between farmer and herder was re-established,

although the context of this relationship has subsequently changed. (See below) It is, perhaps, rather strange to discover that current plans to "develop" the pastoral sector are still couched in terms of "settlement schemes". Especially since, thirty years on, the immigration of Fula herders into Sierra Leone has reduced very considerably. Furthermore, local ties between farmer and herder have, in many areas, strengthened during recent decades. Many herdsmen and herd owners are, as I have indicated above, already permanently settled. Unfortunately, this fact is often overlooked. The Cattle Owners Settlement Scheme was not a success, largely because the aims of the scheme were not really relevant to the actual needs and circumstances of the Fula herders. (*17) Yet in the 1980's plans to re-implement a similar scheme were shelved, temporarily at least, for reasons of financial policy rather than more pragmatic reasons. The need to clarify or reform land rights, surely a crucial issue, is not widely discussed. Instead the "problem" is still seen in terms of a need to reduce, or halt altogether the destructive and anti-social mobility of the pastoral nomads. The Koinadugu Integrated Agricultural Development Project (KIADP) is the main development programme operating in the area. The KIADP is one of two integrated agricultural projects funded by the EEC in the North of Sierra Leone; part of an aid package, which included the Makeni-Kabala road project, aimed at "opening up" the northern districts of the country. The KIADP is described as:- "the introduction of improved farm techniques to small farmers, producing rice, cassava, vegetables and citrus, by provision of extension services and farm inputs on credits with a major husbandry component", supported by a programme of feeder roads and well construction. (Schroder, 1984 p.35) The project, which was approved in 1978, got off to "a very slow start", and "experienced protracted management problems for several years". (ibid.) The livestock component included "the upgrading of six veterinary posts in the project area, (see below) the development of Musaia station with its breeding herd, the establishment of six mixed farm units of 120 ha. as an experiment in the integration |

|

137 |