|

|

| CHAPTER ONE AN INTRODUCTION TO KABALA TOWN. |

| Kabala was the base for the majority of my fieldwork observations, so I shall sketch its development and present day layout. |

| |

|

10 |

| i. The journey to Kabala. On a good run, during the dry season, the 78 mile journey by transit bus from Makeni northwards to Kabala takes some two and a half hours; the terrain swiftly alters from the flat open bolilands of the Makeni plain (*1), to undulating hillsides. Even at the height of the dry season the hills remain green and lush, with only the occasional charcoal blackened hill, a visual feature of slash and burn agriculture, or strangely weather moulded inselberg, to break the pleasant monotony of the verdurous landscape. On the bus itself, no one shows much interest in the passing scenes, although, once in a while, heads may turn to view the swamp rice farms, as the road sweeps across a cultivated valley bottom. These rural scenes form a stark visual contrast to the wide iron grey tarmac road that cuts and sweeps its way to Fadugu, through settlements, which have grown astride the road, that range in size from clusters of four to five traditional grass huts, to small 'towns' of fifty or more rectangular mud brick houses; rusty red clusters of corrugated iron roofs. Along the road, the bus sweeps past the occasional man or woman going to or from their farm and groups of brightly clad primary school children, exercise book and 2B pencil in hand, who scream greetings or abuse at the passing travellers. The drivers seldom feel a need to apply the brake on this section of the journey. Errant sheep or goats are left to make up their own minds as to which direction they plan to leave the road, and it is only when the occasional small herd of unattended cows are encountered that the driver accepts the need for greater caution. The tarmac road, completed in 1980, terminates a quarter of a mile beyond Fadugu, some twenty-five miles short of Kabala. From here on the road is constructed partly of red laterite and partly of earth. It is full of twists and turns, deep bone-bruising potholes and steep bouldered ridges. This part of the journey, in the rainy season is necessarily driven at little more than walking pace. There are few settlements of more than twenty houses along this stretch of the road; and as the scale of the settlements reduces, so does the view! The narrowness and twistiness of the road, necessitates frequent use of the horn, and the increasingly steep hillsides, which seem to draw closer the now more extensive undergrowth, constrict one's view of the country to what lies on the road ahead, and what one has passed. A number of rude wooden bridges are crossed with caution; over-confident drivers are reminded by vociferous passengers of recent fatal accidents. This latter stretch of the journey is seldom completed in under an hour and a half, so it is usually with pleasure and a sense of relief, which passes visibly amongst the passengers, that the overcrowded, and certainly misnamed, 'comfort bus' climbs the last ridge and turns down towards Kabala. The bus halts at the police check point of 'One Mile' just outside Kabala, and conversation, subdued by the painful tedium of the journey, begins again. Limbs are stretched, luggage is checked, children retrieved from helpful companions, and the fare money is collected, amid much protest and complaint. Finally, when all the financial wranglings are settled, the bus completes the last mile, and comes to a halt near the market centre. |

|

11 |

|

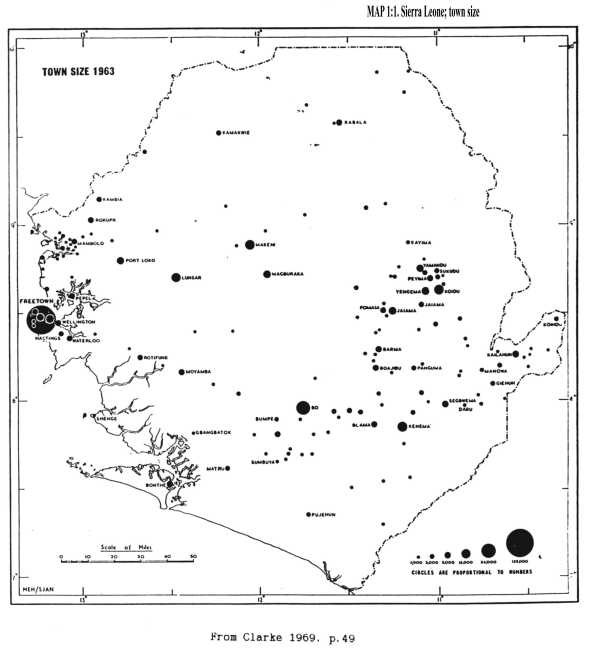

MAP 1:1. Sierra Leone; town size |

|