|

|

| We moved straight into student accommodation at Fourah Bay College, where we were to spend the next three to four

months. This period was one of growing uncertainty and frustration. The inevitable problems regarding the payment

of my stipend were not helped by the unexpected temporary closure of the college. As seems to be usual, things

slowly sorted themselves out, the college was reopened shortly after Christmas, and my stipend reassessed. During these quiet and, sometimes, lonely months I was able to narrow down the range of possibilities for my fieldwork site. A misplaced sense of pride encouraged me to look to hitherto under-researched areas. I longed for originality, and like the explorer Winwood Reade, had the secret desire "to make a name for myself". I knew that extensive research had been carried out among the Limba, Temne, Mende, and Koranko, but that less information had been obtained among the Susu, Loko and Yalunka. It was by reading Donald's thesis on the Yalunka (Donald 1968) that I "discovered" that there were also large numbers of Fula living in the North of the Country. This fact had escaped my attention, during the small amount of reading preparation that I had managed whilst in England. I grew quite excited when I realised the paucity of ethnographic data available on these Sierra Leonean Fula. When I read of the historically based strained relations between the agricultural Yalunka and the pastoral Fula, I grew more so. This seemed rather dramatic and familiar; I recalled the many East African studies I had read whilst in Manchester and mention of farmer-herder conflicts. I was drawn, almost instinctively, to this northern cattle area, to engage in a topic with which I felt some prior intellectual understanding. From the map I pinpointed five or six towns that best appeared to fit the bill for a "small town study" that, at the same time, fell within the northern cattle area. I planned an exploratory trip up North, during which I hoped to visit all the towns I had under consideration. As it was I merely passed through Kamabai and Fadugu, situated as they are on the Makeni-Kabala road, and I didn't travel further North than Musaia, one of the other towns on my list. By the end of that first brief visit to Kabala, my mind was seemingly made up. On returning to Freetown I wrote that as far as I was concerned the decision regarding my fieldwork site had been made. What factors, I asked myself, were involved in that decision? Clearly, "the outstanding beauty of the place" had made a big impression on me. I observed that "Musaia Compound had seemed like rural England on a marvellously hot summer's day" and that "the people were friendly". In a more practical vein I listed Kabala's various amenities, which included three recognised secondary schools providing hope that Esther would be able to find teaching work. I finished my entry by blandly observing that it seemed to be "a nice town in which to live". "Anthropologically", I admitted, "the trip was a more ambiguous success." My first reaction had been that Kabala was too large, and Musaia too small to match the requirements set out in my research proposal. Although I was rather concerned not to give an incorrect impression to the Sierra Leonean authorities that I had come under "false pretences", my enthusiasm for Kabala seems such, that I felt it necessary to put aside some aspects of my original research proposal. In my journal |

|

4 |

|

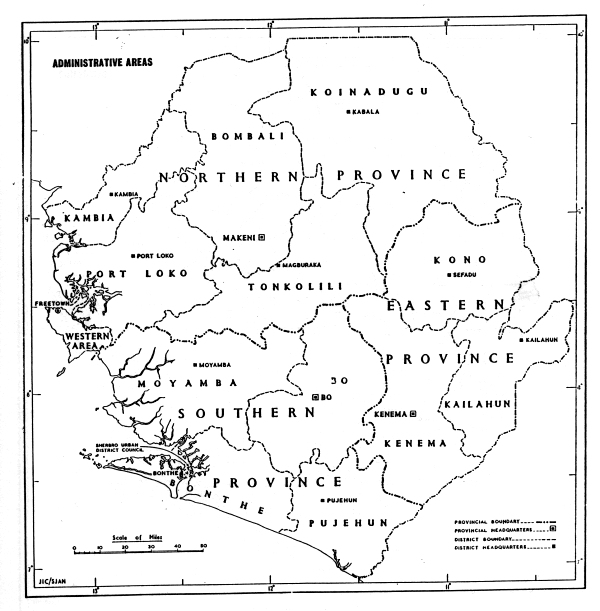

MAP 0:3. Sierra Leone; administrative areas. |

|

|

From Clarke 1969. p.29 |

|

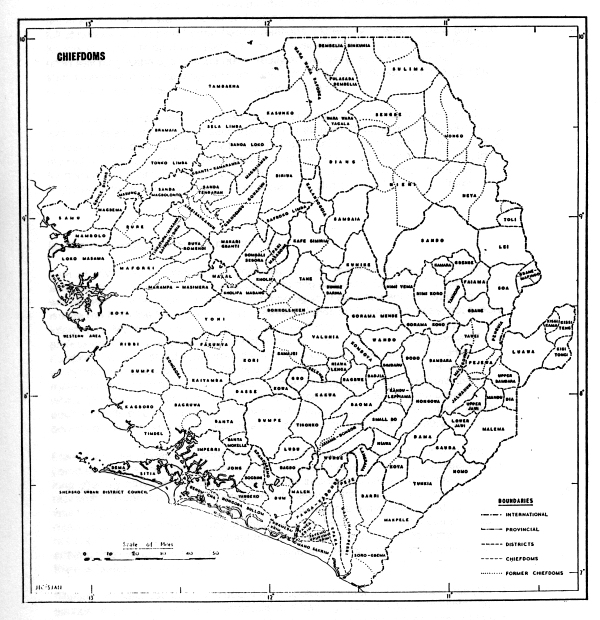

MAP 0:4. Sierra Leone; chiefdoms. |

|

|

From Clarke 1969. p.33 |

| I wrote, "This idea of a holistic small town study, or rather the need to complete such a study, is proving

both irritating and confusing". However, my plans to research in Kabala were supported by Dr. Moses Dumbuya, my supervisor at Fourah Bay. He commented that the area was one of rapid development and change. He was familiar with the area, having carried out research into some of the socio-economic effects of the Makeni-Fadugu road. The decision was ratified and research permission granted. I knew where I was going, but I was not at all sure what I was to do when I reached Kabala. For whilst my head was now full of notions concerning farmer-herder relations, I knew that I was officially going to Kabala to complete an urban based study. I never did resolve this difficulty. In fact, upon reaching Kabala, the issue never really arose. Very rapidly "problems" stemming from my initial proposals vanished from my mind, driven, perhaps, by the base empiricism of the "reality" that now confronted me! I chose to live in Kabala, and I chose to work among the Fula. But after reaching Kabala, it seems as if I took a secondary rather than the leading role in the decisions concerning the directions that my fieldwork was to take. In retrospect, I like to think of my self as having chosen to swim with the tide rather than against it. I still think, that for myself in the circumstances it was the correct decision. Next time I have the opportunity to carry out fieldwork, I am certain my strategy will be rather different. iii. The research: choosing a methodology. I am a fairly confident person and, generally, feel at ease with strangers; I did not feel at all worried about moving to Kabala and starting fieldwork. On the other hand, I was worried about acting out my role of "anthropologist". I did not want my "work" to isolate me from the local community: I wanted friends and acquaintances, not simply informants. My initial lack of confidence as a professional or, perhaps, in my profession, directly affected my style of research and "methodological approach" in a number of ways. I shied away from the formality of work schedules, structured interviews and questionnaires. Pencil and exercise book were, I think, the only material tools of my trade. I took few photographs, especially inside Kabala itself, where the sight of a camera would either elicit scowls of contempt from unwilling adult subjects or else loud cries of "snap me! snap me! snap me!" from the score of bouncing children who would quickly assemble and grin down the camera lens. (*1) From the outset, I was very concerned to understand how I would be able to turn personal experience into anthropology. I can recall a letter I wrote to a colleague not long after my arrival in Kabala; in it I stated my intention to carry out "honest research". "Honest research" sounds unfortunately pretentious to me today. I think I was trying to sound positive. Perhaps I was putting on a brave face; I had intuitively rejected more formal techniques of data collection because I realised that they did not suit me, but I was not sure what I had left. I was very unsure where the anthropology would come from. I think I realise why so many researchers find that there is "safety in numbers". "Participant observation", is the social anthropologist's method par excellence (*2). It sounds very grand in research proposals and training manuals but in the field, the thought that I was "doing" participant observation, was seldom a great comfort to me. |

|

5 |

| But I persisted. I spent much of my time in the company of other people; sitting in the "parlour" or,

more usually, on the verandah. I did not "do" a great deal. My participation was usually passive. I did

not learn to plant rice, milk cattle, nor extract palm-oil, and I did not learn a craft or a trade. But I did spend

a lot of time asking questions. I asked questions on as many topics as I could think of, but seldom were these questions "original". To a large extent I asked the sorts of questions I assumed an anthropologist should ask. I was much influenced by the classical ethnographies, and somewhere in the back of my mind I had a list of chapter headings and sub-headings, which I referred to on occasions to ensure that I was covering the ground. On the other hand, my questions were usually prompted, in the first instance, by the events that took place around me; for example, questions on marriage and divorce at the mention of a wedding. I would then follow up my enquiries, out of context, if need be. I usually wrote down the answers to my questions at the time they were given to me. These notes, which were usually scribbled at great speed, seldom remained decipherable after a few days, so I copied them into further exercise books to make sure they were legible. I did not order my entries in any way, and they remained as they were initially gathered, in chronological order. I did not hide the fact that I was researching and explained, as best I could, what I thought this entailed. No one seemed to mind my incessant scribbling, and on occasions I would be asked to read aloud what I had written, to make sure that I had got the facts straight. I can recall only one occasion when my presence was objected to, and that was a case of mistaken identity. A young market trader, taking me for a Peace Corps Volunteer told me I should go home. "We don't want your help", he retorted. I explained that I had come to learn not to teach. In retrospect, I think I shirked the real issue. Although I did not have enough money to employ a research assistant, over time, a few individuals began to appreciate the kind of understanding I was looking for. By the end of my fieldwork I found that I had cultivated a small number of "key informants" who were willing to volunteer their own information and offer interpretation of the days events. Nonetheless, I continued to maintain a wide range of social relationships. I never found access to the "domain" of women a real problem, for reasons that will become clear below. But I did rely on Esther a great deal, to ask the questions which would have been inappropriate coming from a man. I began my fieldwork with the intention of gathering "general ethnographic data", however, my research remained largely unfocussed. And, whilst I became increasingly interested in cattle husbandry (see above), my social ties to Kabala town, where I spent the majority of my time, limited the extent to which I was able to pursue this specific line of research. My fieldwork notebooks remained unstructured to the end, although later entries were often longer and my observations more sustained than those made early on. I lived in Kabala for about eighteen months. Personal difficulties between Esther and myself led to a hasty, and with regard to my research, an unsatisfactory departure. I did not have time to tie up "loose ends" and, subsequently, came away with the feeling that my research was flawed and incomplete. But even under different circumstances, saying goodbye to Kabala would have been difficult. I could not have left without experiencing a sense of loss and sadness for those I had to leave. |

|

6 |

| iv. The thesis The bulk of this thesis was written between April 1987 and August 1988. The delay was unfortunate but, I think, unavoidable. Since leaving Sierra Leone in mid-1985, I have been unable to keep in close contact with my former friends and acquaintances. Occasional letters have been sent and received, but their highly formal, stylised format, I fear, make for dull reading. They are "greetings", and as such, convey little news. The ethnographic data relating to Kabala presented in this thesis, then, stems almost entirely from my fieldwork experiences. The shape or structure of the completed thesis is, quite frankly, not what I had intended when I first set out to write. Some time after my arrival back in the U.K., I photocopied all my notebooks. I then sorted them out by subject, corresponding, by and large, to the chapter headings of a standard ethnography (see above). I had a file on "kinship", "marriage", "religion and belief" etc.. But little of this information is presented here. The thesis follows a rather meandrine course through my fieldnotes, but I hope the end result provides a more accurate, dare I say "honest", representation of my fieldwork, than, perhaps, a more orthodox account. The thesis moves around, without centring solely upon, a single individual, Haja Aisaitu Bah. The details of her life are not given here as they are fully discussed below. In brief, I became a quasi-member of Haja's household. I became dependent on her for many of my basic necessities; a place to live, food and, on occasions, money. Through my incorporation into Haja's household, I found myself in a position to observe and participate in Fula society. My acceptance by Haja gave me status as an honorary Fula, and allowed me to form many relationships within the community. But, it was my relationship with Haja which legitimised my presence. Haja's unexpected death, towards the end of my fieldwork, affected me deeply. As I came to write, I found that my memories of Kabala centred around my memories of her, and this provided the framework around which the thesis was written. The result has been a somewhat "personal" piece of writing, but I do not find this inappropriate. Against this, I feel I should stress that this is not really a reflexive anthropological account. Inevitably, my fieldwork experiences taught me a lot about myself, but "the lessons learned" are not repeated here. 'I' appear occasionally in the text, but my presence is largely incidental. My primary interest in social anthropology is to understand the lives of other people. I shall now attempt to sum up, in broad outline, what my intentions have been in writing this thesis. I have chosen to concentrate on a limited number of actors through which I could convey the flavour and, perhaps, the meaning of a particular social setting; namely, a small town in Sierra Leone. The actors that appear are, to a greater or lesser extent, represented as characters, rather than examples, types or categories. Indeed, as I have already indicated, I found formal categorisations and survey-type classification to be inappropriate to my fieldwork conditions. I have tried, where possible, to ensure that the actors are seen in a proper context; against the backdrop of a range of general social issues which relate to the rapid social changes that are occurring within Sierra Leone society. However, I do not pretend to provide a holistic analysis; the town was not my object of study, but simply the context of my observations. At best, I offer a "slice of life", although I hope this partial representation will be seen to have a "wholesomeness" of its own. |

|

7 |

| By adopting this approach, I am not rejecting the styles or methods of other scholars of "small towns in Africa".

The study of "a strategic elite" (Vincent 1971), "the culture of friendship" (Jacobson 1973),

"the problems of...poverty crowding and criminality" (Bjerén 1985) or "changing social institutions"

(Brokensha 1966), for example, each entail a separate approach; yet all these studies serve to enlighten our understanding

of small towns. I hope to have made a small contribution by adding a further dimension. v. A summary of the main chapters. The thesis is divided into eight chapters, followed by a short conclusion. In Chapter One I provide some background information on the growth and development of Kabala town, as well as a description of its present size and shape. Fula are regarded as "strangers" in Sierra Leone, and often classed as "Guineans" and recent migrants. But I demonstrate in Chapter Two, that migration of Fula traders and herders into the area which is now Sierra Leone, has taken place over centuries. In Chapter Three, I introduce Haja Aisaitu Bah. I provide a detailed description of the composition of her household and then examine the ways in which she was able to maintain an independent household in the face of conflicting claims on her property. I argue that it is difficult for a woman to control her own resources without the intermediacy of a man. In Chapter Four, I examine how two male migrant traders have established permanent households in Kabala. Nonetheless, I observe that mobility remains an important aspect of Fula social organisation. In Chapter Five, I observe how increasing numbers of "traditional" Fula herd-owners are settling in Kabala. I also discuss some of the ways in which Fula sub-group identities are changing. In Chapter Six, I describe Haja Aisaitu Bah's cattle camp. I also examine the ways in which Kabala-based traders are able to invest in cattle. In Chapter Seven, I look, in greater detail, at the commercialisation of cattle production. I discuss Fula involvement in the livestock trade and examine the strategies of a relatively unsuccessful livestock trader. In Chapter Eight, I examine the attempts which have been made to "develop" the livestock industry. I argue that a number of fundamental misconceptions about Fula pastoralism persist. Finally I reflect upon the impact that national politics has had on herder-farmer relations and suggest that conflict between Fula and Yalunka can no longer be "solved" at the local level. |

|

8 |

| Notes to preface 1.) By accident rather than by design, I find myself in good company. Bohannan (1957) warns of the dangers of gadgetry "introducing a false note into the flow of social life". He reflects:- "The only sensible gadget for doing anthropological research is human understanding and a notebook. Anthropology provides an artistic impression of the original, not a photographic one. I am not a camera.". (Preface, vii) 2.) It is not my intention to add to the debate on methodology; I simply wish to give an impression as to how I spent my time in the field. For a recent overview on the principles and practices of "participant observation" see Hammersley and Atkinson (1983). |

|

9 |