| PREFACE. |

|

i. The "original" research proposals.

Early in 1983, I wrote, with the assistance of Dr. Paul Baxter, my tutor at Manchester, a research proposal entitled:-

"A social anthropological analysis of a small urban settlement". Two, broadly similar, versions were

written. The first, the shorter of the two proposals, was presented to the Association of Commonwealth Universities.

The slightly longer version was subsequently presented to the trustees of The Emslie Horniman Anthropological Fund.

It is the latter version which I present here.

"I am interested to see how Social Anthropology can assist development; at the risk of sounding presumptuous

I would hope my work could be useful. Sociological and social anthropological research in West Africa has tended

to concentrate either on the more populous areas or the remoter hinterlands. It is becoming more and more apparent

that the small towns, in which so many people gain their first urban experience and in which health centres, schools

etc. are built, have been crucial centres of development and change; but their study, especially in West Africa,

has largely been ignored. As Epstein pointed out in his essay, Urban communities in Africa (1957), while external

forces are continuously moulding local communities, it is local communities which determine how such external forces

will be received. A recent special edition of Africa (49.3.1979) draws attention to this gap in our knowledge.

I aim to make a holistic study of a small town which has grown up around a road or former rail junction (the railway

tracks have been ripped up), and/or around a market or administrative centre. I intend to follow leads from the

comparable East African studies bearing in mind the work in West Africa of scholars such as Mabogunje, Dumbuya

and Hill. I am particularly interested in examining how diversification in labour opportunities, changes in productive

activity and marketing techniques have affected family life. There is a rich store of traditional ethnographic

data on the peoples of Sierra Leone, (Little, Littlejohn, Jackson, McCormack, Cosentino, Finnegan, Ottenberg etc.)

but little recent work on the changes taking place in rural/small town life.

It is difficult to delineate a research proposal in detail, while I am still totally in the dark as to what funding

I shall actually have or what my local costs will actually be. Even with a contribution from Horniman I shall still

be extremely hard up. I shall not have funds for any local assistance nor for much travel etc. I must needs rely

on the observations my wife and I can make within walking distance of where we settle to work. I shall have no

options but to follow my present intentions and concentrate on observations of daily life in a small town.

Rather than speculate about what I shall actually be doing it seems more sensible to indicate what led me to wish

to study a small town and some of the general problems which seem likely to be of interest. My impression is that

it is in small towns, Middleton's type C, that changes in institutionalised

|

|

1

|

| |

social relationships and the creation of new types of relationships can actually be observed. Small towns are

really where the action is. Many authorities (e.g. Gutkind, Bailey, Wolf) have urged the study of small towns,

but there have been few such anywhere in Africa and none (apart from the unpublished studies of Butcher and Dumbuya)

of towns in Sierra Leone. Little from his Sierra Leonean experience long ago pointed out that it is the local teacher

or dresser who provide the models of modernity for rural aspirants. But this lead has not been followed.

I have been strongly influenced by Southall's Introduction to the "Small towns in African development"

special issue of Africa (which is a summation of his earlier work) and Joan Vincent's publications on Gondo in

Uganda (esp. African Elite: the bigmen of a small town 1971). I have also been influenced, though to a lesser extent,

by other East African studies such as Anders Hjort's Savanna Town (1979). And D.Jacobsen Itinerant Townsmen (1973).

Southall and Vincent open up ways of understanding the ethnically varied elites of the town, such as teachers,

mechanics, agricultural instructors, traders etc. (My hunch is, following Sudanese leads, that traders and barkeepers

could be a crucial link between the two).

Joan Vincent's statement that:- "The small town provides a micro-cosmopolitan urban environment in a culturally

homogeneous rural setting" sums up my interests. I am seeking a field situation in which the number of persons

are manageable and the cultural variables limited but in which there is a span of social differentiation.

Vincent establishes for Gondo, and I suspect that this is generalisible, that competition for prestige and power

between local "Big Men" centres on the competition to mobilise labour, and that should be observable

and checkable.

Vincent also notes that in most developing countries, it is the police and army who are the "critical arbiters

of political events"; yet no one seems to have studied, at the level of the local police post or the NCO on

leave, how policemen and soldiers (who are mostly of rural origin) actually interact in day to day life with small

town and rural citizens.

Schooling and local paid employment, it is reasonable to suppose, must both have modified age and sex differences

as principles of social differentiation. Unemployed school leavers have also been defined as a "problem"

throughout West Africa since, at least World War I, but what they actually do in the country and the small towns

has hardly been described, except in novels such as Cameron Duodo's Gab Boys.

I anticipate spending some months at the Department of Sociology at the University of Sierra Leone, during which

I should start language work, familiarise myself of the particular knowledge of my supervisor Dr. Moses Dumbuya

(whose own thesis was on a company town) and the staff of the Department in the selection of a town. I should then

hope to spend at least a year at the field site, conducting my research by participant observation and using the

usual methods and techniques developed by social anthropologists. Assuming that a major task will be the recording

and unravelling of interlocking networks, I shall need to keep systematic records on individuals.

|

|

2

|

| |

For this purpose, I intend to adapt the Manchester record card. I shall aim to learn Mende or Temne and hope

my wife becomes expert in Krio. I shall make a particular effort to place the study into the wider national perspective

of development and change because, presumably, external events and governmental constraints are likely to be felt

more immediately in a town dependent on a market than they are in the countryside. But I do not want to get so

trammelled in the macro-scene that my own observations lose their centrality."

|

| |

ii. The choice of a fieldwork site.

When I arrived in Freetown in November 1983, I was in many ways unprepared, both as a person and as an anthropologist.

(*1) I was accompanied by Esther, at that time my wife, who had spent her early childhood in Ethiopia and more

recently had visited Kenya. By contrast, apart from a week-long school trip to France, I had never travelled outside

the United Kingdom.

I had rather hoped to have gone to East Africa; whilst at the University of Manchester, where I completed my M.A.

in social anthropology, I had become very interested in East African pastoralism. My pre-fieldwork interests were,

inevitably, greatly influenced by those of Paul Baxter and other members of the department. However, government

cutbacks in higher education affected my plans a great deal. It was "economic rationality", rather than

intellectual reason, that forced me to apply for any grants for which I was eligible. I was most fortunate in being

awarded a Commonwealth research scholarship to carry out research in Sierra Leone. The research proposals that

I produced on a small town study were not "dishonest", they were both practical and relevant. However,

it is true to say that, at that time, my major interests lay in pastoral societies.

The offer of the award was confirmed and finalised between August and September 1983, leaving me with very little

time to prepare for my visit. I arrived at Lungi airport with my recently purchased ethnographies on the Mende,

Kuranko, and Krio packed at the bottom of my suitcase, largely unread.

What I lacked in specific local ethnographic preparation, was offset by the general training I had received whilst

at Manchester, and was probably made up for in my enthusiasm. I recall a sense of accomplishment and relief that

I had at last achieved my goal of undertaking fieldwork. As the ferry groaned its way from the Lungi peninsula

towards Freetown, I remember feeling calm and confident. I was not at all worried by my unpreparedness, on the

contrary, I took a queer pride in my ethnographic "innocence". I felt uncluttered by my lack of preconceptions

about Sierra Leone, and I was pleased to be experiencing everything with what I then took to be an open mind. By

the time the ferry had reached the Kissy terminal I had almost convinced myself that it was better to be unprepared

than to begin fieldwork with a muddled hotchpotch of other people's ideas and observations. It was, for both of

us, a time of great promise. |

|

3

|

| |

|

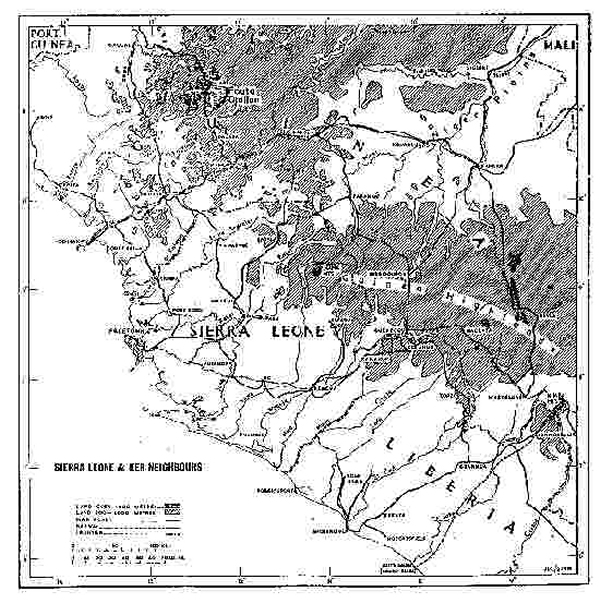

MAP 0:1. Sierra Leone and her neighbours.

|

|

|

| |