i. Pastoralists and the Futa state.

By the end of the eighteenth century, a powerful Islamic state had developed in the highlands of Futa Jallon.(*1)

Futa Jallon, formally an area of ethnic heterogeneity, came to be ruled over by Muslim Fula. The success of a jihad

led to the displacement of a great many people from their former homelands with, for example, non-Islamic Susu

and Yalunka being pushed southwards towards what is now Sierra Leone. (Kup 1975,p.45) But Futa Jallon was also

occupied by non-Islamic Fula pastoralists and, as Suret-Canale notes, it was against their own co-linguists that

the Islamic Fula were to launch their fiercest attacks.(1970,p.79) In general, however, the dispersal of these

various populations is not well-documented. Whilst some Fula moved away from the growing sphere of Islamic influence,

others became incorporated, to a greater or lesser extent, into the powerful Islamic state. (cf. Quinn 1971,p.430)

The Fula state dominated much of the region, until it was dismantled by the French during the latter part of the

nineteenth century.

The intricate and complex political history of the Futa Jallon state need not detain us here, although it should

be recognised that the power of the state fluctuated a great deal. Hopewell relates the instability of the state

to its feudal structure. (Hopewell 1958,p.62) Suret-Canale, however, finds the system more difficult to define,

and notes how the state "maintained a certain order through its institutional disorder". (idem p.81)

Nonetheless, it is clear that the threats to the state did not merely come from outside the chieftancy, although

external rivals were to overrun Timbo, the political capital, on more than one occasion. Civil wars and revolts,

some of which had less to do with dynastic rivalry than with ethnic self-determination, also threatened internal

security.(*2)

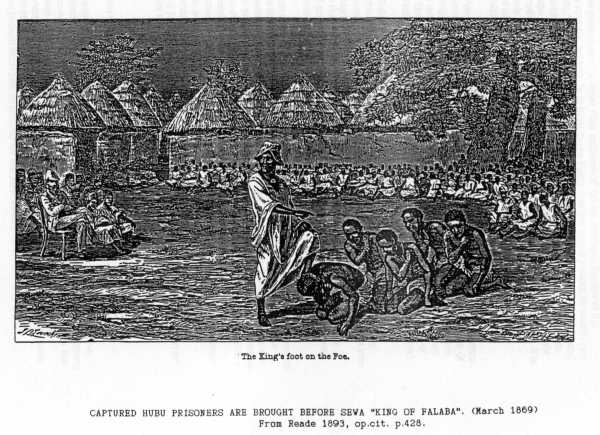

Viellard, in his valuable "Notes sur les Peuls du Fouta-Djallon", mentions a number of these revolts.

Among them, Viellard records "la revolte des Houbbou", pastoralists whom "las des pilleries infligée

... leur bétail se révoltêrent et fondêrent l'êtat peul dissident du Fitaba"

(1940 p.103).(*3)

The Hubu are one of the pastoral sub-groups presently found in northern Sierra Leone. The other named sub-groups

are the Tellico, Kebu and "Sanda Fula". (*4) Viellard makes no mention of Tellico as a group, although

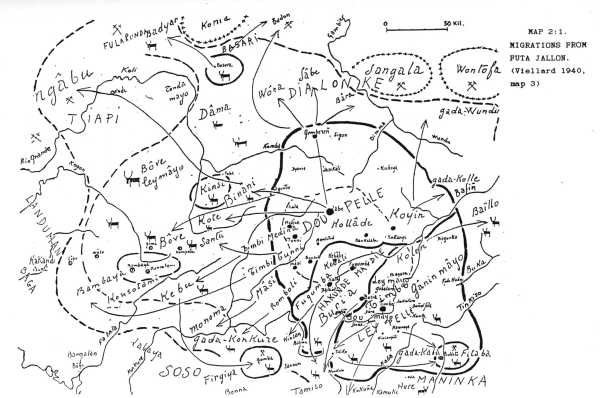

the town of "Teliko" appears on his map. (map 2:1) (*5) On the other hand, "Kebu" does appear

, although it remains unclear, either from the map itself or the accompanying text, as to whether "Kebu"

refers to an area, a "people" or to both. The map would seem to suggest that the people of Kebu too led

some kind of revolt against the state and, leaving the Timbi area, formed an association with the independent state

of Gomba, described by Viellard as "un autre centre de dissidence peule:...cré‚ comme de coutume par

un mystique appuy‚ sur des pasteurs m‚contents."(ibid, 104) But uncertainty remains. On the following page

Viellard mentions that the "dependency" of Kébou became integrated into the Futa State.

What is to be adduced from these scant references? Whilst it is certain that the Hubu have existed as an (historically)

significant sub-group since at least the middle of the nineteenth century, it is not clear whether the Kebu or

Tellico "existed" at this time. The rise and fall of states and empires is often paralleled in the creation

and recreation of ethnic identities, but such changes are often tantalisingly ill-documented, and the degree to

which present understandings can be utilised to enlighten this shady historical past is limited. |