|

|

| Protectorate. Warren, district commissioner of Koinadugu District, writing in 1907, noted the presence of "a

large Fula settlement" on the northern frontier of the Yalunka country, adding, "it is from these Fulas

that the country owes its wealth (viz. live-stock)." (1928 p.25) Lipschutz suggests that the Sierra Leone

cattle market and high French cattle export duties were incentives for large scale Fula migration into Koinadugu

district after the turn of the century. (Lipschutz 1973 p.166) But it is not clear whether these migrants were

themselves actively involved in cattle trading. It is more likely that herd owners were migrating from Guinea in

their efforts to avoid payment of a cattle tax that had been imposed by the French. (See Traoré Ray Autra

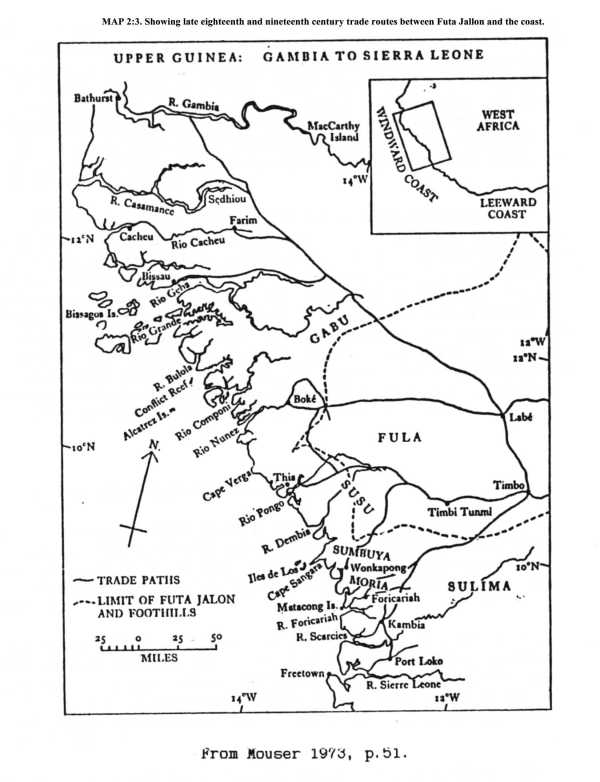

1980 p.428) Under Pax Brittanica, the immigration of Fula pastoralists into the Koinadugu district gained momentum. A census carried out in 1931 records 20,000 Fula immigrants of recent origin living in Koinadugu and Karene districts. (Viellard 1940, p.89) But this number increased many-fold over the next two decades, with Fula settlement from French Guinea being "officially encouraged and assisted", by the administration of the protectorate. (Colonial office reports on Sierra Leone 1953 p.38, but see below) Under Sekou Toure's regime, Fula herd owners in Guinea suffered a variety of violent threats to their lives and property. I was told that many cattle were forcibly requisitioned by the government. During the 1960's "massive migrations" of Fula into Koinadugu, along with thousands of head of cattle, are said to have taken place. (Traoré Ray Autra 1980 p.428) Some families, perceiving an improvement in the general political situation, have since moved back to Guinea, although many others have remained. Migration of Fula pastoralists into the northern districts of Sierra Leone has continued over the last 100 years or so. In general the process has been peaceful, and has been carried out by gradual infiltration rather than by conquest. It would also appear that this progressive movement has been the result of individual rather than collective decision making, although the political uncertainties in Guinea throughout the 1960's may possibly have led to more collective action during this period. Pastoral requirements have meant the dispersal of the cattle herders throughout the northern districts, and they are found interspersed among the "indigenous" farming communities, among whom the Fula have settled, rather than displaced. The resulting pattern is that of a complex heterogeneous mosaic. (Further discussion on this point follows.) iii. "Gold and Hide Strangers"; trade and Futa Jallon. The presence of Fula traders in both the Protectorate and Colony of Sierra Leone dates back into the early nineteenth century. Trading in cattle, ivory and gold, among other commodities, Fula traders provided an important commercial link between the European traders at the coast and Futa Jallon. However, outside of Freetown, permanent settlement, in appreciable numbers, does not seem to have taken place until the twentieth century. Overall, the process of immigration has followed a different pattern from that described for the pastoralists. Rankin, writing in 1834, provides one of the earliest descriptions of a Fula trader in Freetown. (*10) But Rankin's lively portrait, is well matched by a perceptive account |

|

26 |

|

MAP 2:3 |

|