|

|

| Notes to chapter four. 1) In 1953, Alimamy Jalloh was also appointed to be vice-president of all native courts in Koinadugu District. Dougal Reid, District Commissioner from 1952 until 1956, informs me:- "This [appointment] was to ensure that Fulas received a fair deal from these courts in any dispute between a Fula and an indigêne. Jalloh's appointment was a complete success. In my role as supervisor of the Native Courts, I observed that...the courts worked equitably between Fulas and local litigants." ( 1988, Personal communication). 2) See Butcher 1965 p.52-3 who provides similar information. Although they may have originated from towns a great many miles apart, these urban migrants are known collectively as Futa Fula. By contrast, the pastoral Fula are divided into various sub-groups, but also originate from the Futa Jallon region. 3) One day I met a college-educated Fula on the verandah of Alhaji Pita, a respected Fula elder. (See below) The young Guinean had been in Sierra Leone for a year. He told me that he had come "for money", adding that his mother and father had cattle, but "not enough". When I asked if he still owned any livestock he replied "Fula and cattle don't part". He was trading in cattle, buying at Gbindi and in Kabala. The man referred to Alhaji Pita as "family" because they came from the same town. He said this was reason enough to claim a family relationship. He did not plan to stay at Alhaji Pita's house, but through Alhaji Pita he sought to establish local social and business contacts. He contemplated moving into "hog farming" and had visited a local "hog farm", near to Alhaji Pita's "garden" in Malaforia. The young man hoped that Alhaji Pita would use his sababu, ( Kr. derived from Me., benevolence, goodwill, help) and persuade the manager of the "hog farm", a non-Fula, to provide him with further information about the business. 4) What I knew of Alimamy Jalloh, who died in 1980, mainly derives from Haja Aisaitu. Alimamy Jalloh married seven women in all, some of whom continued to reside in Kabala after his death. I was unable to piece together a detailed account of the development of the complex multi-household unit that had formerly existed. Furthermore, due to various intrigues and past disagreements between Haja and her former co-wives, I did not always find myself on good terms with these women. The information provided by Haja was, naturally enough, often biased. Similarly, my close identification with Haja made it difficult for me to spend much time with Alhaji Boie, and at times my relationship with him was very strained. (See above) Towards the end of my stay, especially after Haja's death, our relationship improved a great deal. It is possible that Haja's death, in effect, removed the cause for any animosity that lay between us. However, I prefer to interpret the late improvement in our relationship as an indication of Alhaji Boie's recognition of my sincere attachment to Haja and her "children". 5) It was not usual for Fula to own large "gardens" (Kr.) of this sort. By way of explanation, I was told that the "owners" of the land, the Kuranko and Limba, were less willing than before, to allow Fula to establish permanent gardens of this sort. A similar opinion was offered concerning the use of swamp for rice cultivation. "First time, when there was plenty of land and few Fula, requests to use land were usually |

|

71 |

| granted", so the argument went. But other informants denied that access to land for these purposes was so

difficult. Mohammad Jalloh, a trader, had begun to develop a "garden", two or three miles out of town.

He told me that he had been granted use of the land, through a Limba friend. In his case, it had not been necessary

to make any formal representation to the chief or local headman. It seems likely, however, that in most instances

a more formal procedure is adopted. 6) Alansana and Ousman resided permanently at the warri, but a variety of arrangements can be made. Sam notes:-"Mr. Brima Barri, the most successful Foulah trader in the town [Bafodea] has ten relatives staying with him. These relatives always change duty on the worrehs. [alternative spelling] That is to say after every two weeks those who have been in the worreh return to Bafodea and are replaced by others from the town. In going to the worreh, cattle keepers take along rice, palm oil, soap, and a few tablets like Codeine." (1984, pp.10-11) 7) Alhaji Pita did not remarry after the death of his third wife. One informant said that the deaths of the three women, though not Alhaji Pita's fault, occurred as a result of their marriage to him. The informant suggested that there was something "inside" Alhaji Pita that was dangerous to women, possibly some kind of djinn (jinna, F.), and said that Alhaji Pita had, in not remarrying, followed the wisest course. 8) My data shows that family marriages and "cousin marriages", in particular, are commonplace among the Fula. However, I discovered that there was no general agreement on the "guidelines" for such marriages. Many informants contradicted each other's statements on the matter, and I often found that my informants' views were not in accordance with the information on actual marriages I had collected. Some people, Haja included, became confused when they attempted to generalise about whom one could and could not marry; although many could elucidate by naming specific family members and explain why thy fell into one or other of the two categories. Other informants, including Alhaji Boie, had a very clear idea: "It's simple", Alhaji Boie explained, as I grew more and more bewildered by Haja's lengthy and involved examples, "a man's children cannot marry the children of his brother, and a woman's children cannot marry the children of her sister". In other words, Fula do not marry their parallel cousins (reme,F.) but marry their cross cousins (denda,F.) But marriage between a man and his father's brother's daughter (FBD) does occur; some informants suggested that it was more common among Fula herders than among Futa Fula. FBD marriage certainly took place within Haja's close family. I did not come across a single instance of marriage between a man and his mother's sister's daughter. I often found the confusion that resulted from my enquiries on cousin marriage most informative. Whilst some informants would reach for their Koran for guidance, in other instances, my questions would result in animated, but never heated, debate between those whose opinions differed. 9) Coto Jaila told me that he had accumulated the capital to establish the table during the years he had been engaged in cattle-trading, and it had been his intention to leave the table entirely in the hands of his wife. As a result of a financial set-back, Coto Jaila had so far been unable to do this. Nonetheless, he still regarded the table as belonging to Binta, his wife, and still intended to hand this business over to her as soon as he had developed another profitable enterprise for himself. |

|

72 |

| 10) Most of the wood in the market-place, was sold by Limba women. I did not learn of any Fula women engaged in

this particular activity. One of Haja's neighbours cut wood to be used for building poles. He also collected locally-recognised

medicines, but did not gather firewood. Every few weeks Haja was visited by a poor and partially blind old man, who brought a large bundle of firewood. In his younger days he had worked for Alimamy Alhaji A.R.Jalloh. Haja told me that he had been a good worker, but when his eyesight had failed him, he had been unable to continue working with the cattle. Although Haja always gave him some money, and usually something to eat, the wood he brought was ostensibly a gift, and given out of "respect". He visited Yogomaia Mosque every Friday where he begged for alms. After the service he would visit certain people in Yogomaia, Haja and Alhaji Pita included. I never heard this man ask for money. He would simply greet his host, usually from the verandah, and exchange a few words. Before they parted, the host would invariably give a small amount of money to the man. The money was always accepted with a short blessing of thanks. Although the man was especially poor, and therefore took no part in the affairs of the community, I noticed that he was always treated with respect. His position was regarded by the others as unfortunate, but not of his own making. 11) I asked Coto Jaila whether children ever stayed with their mother, following a divorce. Not, he explained, if the full marriage payments, and in particular, tene, the bridewealth, had been paid. Coto Jaila likened tene, which consisted of a payment of gold and/or cattle, to "insurance". Coto Jaila had told me that his mother was now responsible for looking after his son. However, she was not accompanied by the child on her visit to Sierra Leone. I did not think to find out what alternative arrangements had been made. 12) Like Coto Jaila, Momadu Bailor [ii] had already pursued a number of careers. Momadu Bailor's father had died whilst Momadu was still young. He told me that he had left his home in Mamou, Guinea, because he was unhappy. I gathered that his unhappiness was related, in some way, to his father's death; but he was not specific. From Mamou, he went to Dalaba where he found employment in a cattle camp. He worked here for seven months but left because he wasn't being paid. He travelled to his married sister in Kono, Sierra Leone, where he was found an apprenticeship to a tailor; traditionally a male occupation and a popular career to which many young men aspire. (See Schultz, 1984, p.55) He worked as a tailor in Kono and then Freetown for six years before moving to Kabala. 13) My friends and acquaintances certainly did move around a lot, and members of Haja's household were constantly coming and going. (See above) Even Haja made a couple of lengthy trips to relatives in Freetown, leaving me to mind the house. Ostensibly these visits were for "medicine", however, I think it is likely that Haja's trips were also designed to provide a break from the wearisome responsibilities of running the household. The "effect" of this constant coming and going is hard to characterise. However, travel has the effect of extending one's knowledge of the world and one's intellectual horizons, and this may partly explain why I felt the Fula to be so cosmopolitan and open-minded. |

|

73 |

|

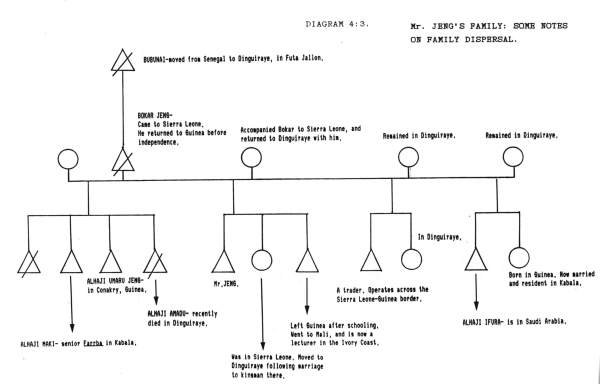

DIAGRAM 4:3 |

|

Mr. JENG'S FAMILY: SOME NOTES ON FAMILY DISPERSAL |

|

| 14) Unfortunately, I do not recall who made the comment concerning "the Jews of West Africa", and I cannot

remember whether the purpose of the metaphor was to draw attention to Fula wealth, their history of migration,

(i.e. the wandering Jews,) or both. The reference to the Jews is interesting since it brings to mind certain other

comments made concerning Fula origins. I was sometimes told by the Fula that they were white, and that they had

originally come from "white man's land". Some informants stated that the Fula had descended from Arabs,

and one suggested that the Fula were the missing tribe of Israel. And see Stenning (1959, p.18ff) who provides

a brief discussion of the widely divergent hypotheses of the origin of the Fulani. A number of writers, listed

by Stenning, affirm their Jewish or Syrian origin. (p.18-19) Incidentally, the Fula regard the neighbouring ethnic groups as being black: they refer to them as balebe, black people. (Also noted by Hopen 1958, p.2). 15) The example of Mr. Jeng's family, which is shown on diagram 3:2., may be extreme; however it is certainly not unique in the extent to which dispersal, especially among the "Futa Fula", has taken place. However, I should also note that Mr. Jeng came from a family of praise-singers, (farrba, F.), which may partly account for the rapidity of the family's dispersal. Traditionally, praise singers were clients of chiefs and other big-men. Mr. Jeng told me that his father and grandfather were frequently given gifts of cattle, but did not build up their own herds, preferring instead to exchange their cattle for goods or money. Such prestations apparently occur less often these days, and Alhaji Maki, Mr. Jeng's elder brother, now has his own cattle camp. Mr. Jeng is not a praise singer himself. He told me that he had "come out". But I am certain if he had wished to remain a farrba, it would have necessitated a move to another town. One locality can only support a limited number of clients of this kind. 16) Or her husband's family. I do not know what form of post-marital residence is most common. The situation is complicated by the fact that I was researching within a recently established migrant community. Uxorilocal residence is unusual. 17) Dupire notes of the WoDaaBe:- "It is always her natal family that a woman relies upon, until such time as her sons are married. She often leaves the small livestock which are her personal property with her father, not trusting her husband to look after them. She frequently visits her family, and returns to it when unhappy, widowed, divorced, or when suffering from a long illness, to find the support she has need of. The husband is well aware of this constant admonitory threat which hangs over him. The supervision from a distance which his wife's kin continue to exercise over her own well-being and that of her livestock is reason enough to induce him to treat her according to the rules of customary law". (1963, p.74) Dupire's comments apply, I think, equally to Fula herders of Sierra Leone. 18) One or two women inferred that it was a wise thing to keep one's cattle with one's own family, suggesting that a husband is likely to "eat" a woman's property. A woman is more likely to achieve some degree of financial independence from her husband through the reproduction of cattle inherited from the family herds, than from the more limited rights in her husband's livestock which were invested in her at marriage. Of course, distance is important here; the distance between the cattle camp of her husband and her own family, may prevent a woman taking her cattle from the family |

|

74 |

| herd with her upon marriage, although she could always sell them. On this point, see Haja's difficulties. (Chapter

three) 19) With years and, maybe, increased resources, elders can let some routine tasks devolve on subordinates, but still retain "business" control. Some of the elders, particularly the close associates of the present Fula District Headman, continue to travel around a great deal on "business". The Fula District Headman is responsible for the Fula in the entire district and frequently relies upon representatives, chosen from his close acquaintances, to hear cases, settle disputes, attend burials and so on that take place outside Kabala. On the other hand, elderhood is, for many, a time of increased religiosity. It was regarded as "fitting" that once an elder had become a chernor or gone on the hajj, he should choose, like Alhaji Pita, to lead a quiet, simple and contemplative lifestyle, conducive to keeping a "cool heart". 20) Haja flew to Saudi Arabia; there is a company in Freetown that specialises in chartered flights for pilgrims. Coto Jaila said it was still possible to travel overland, but I did not come across anyone who had completed the hajj in this manner. Pilgrims from Kabala journey together in small groups made up of friends and/ or family members. Haja travelled with her husband, but the group included friends of her husband and, I think, their wives. Alhaji Pita travelled with two men; a local acquaintance and a relative from Kono. 21) Usually, but not always, through scholarships. I learnt of two local Fula women who were taken to the United States by Peace Corps Volunteers, who had worked in Kabala. The first woman had borne the volunteer a child, I think, during his stay. He took the child back to the United States with him, and later returned for the mother. During my fieldwork an American volunteer took as his girl friend a young Fula primary school teacher, who subsequently "became pregnant". I was told by my own informants that this was untrue. At first she insisted that she wanted the child and the volunteer insisted on an abortion. She agreed to have an "abortion" so long as he helped her get to America, which he did. I do not think this instance is unique. 22) cf. Foster 1965, especially chapter eight. 23) Many Fula children only complete their education after having attended a number of schools; parents may move from one area to another taking their children with them; children placed with kinsmen for schooling may rejoin their own parents as domestic circumstances alter; financial difficulties may lead to a pupil being temporarily withdrawn from one school, and later restarting at another. Furthermore, secondary schools are few and far between, (although there are three in Kabala). However, progression through school is dependent upon attainment, officially at least. If a pupil "fails" at one school, it is common practice to try again at another. 24) Although I have but a few examples to hand, it appears that nowadays many Fula who travel abroad appear unwilling, or unable, to maintain close contact with their families; which may explain the reluctance of many parents to encourage their children to go overseas to study. However, examples from elsewhere might show otherwise. One of Haja's relatives in Freetown had married a Fula man already resident in the United States. Transatlantic marriages may be frequent among established Fula families in Freetown. |

|

75 |

| 25) For instance, Haja's neighbour, Coto Timbi, whose son wanted to study in America, told me that he had made plans to send his son to a kinsman in Monrovia, in order that he should learn to trade. |

|

76 |