|

|

| Bailor [i], a resident of Kabala and a kinsmen of the deceased man. Momadu Bailor [i] is also from Tougu‚. I have

recently been informed that Binta has borne a son. Coto Jaila occupies a room in the compound of one of the Yogomaia elders, Chernor Brasi. Coto Jaila formerly paid rent on this room, but the elder waived the payment on learning that Coto Jaila's mother originated from the same small town as himself, and could thus be considered as "family". During the course of my research, Coto Jaila's mother arrived from Guinea, and was given a room in the household, and was still residing there, four or five months later, when I left Yogomaia. I did not learn of any arrangements which would indicate that she planned to settle with Coto Jaila on a permanent basis. However, for some time before her arrival, Coto Jaila had expressed concern for his mother's well being. Coto Jaila told me, "if she was at rest, it would help me see clearly in my business". It would not be unlikely for Coto Jaila's mother to take up permanent residence with him, since he is her eldest surviving son. Binta's brother, also called Momadu Bailor [ii], lives in the room next to Coto Jaila. He shares the room with Ousman, an apprentice carpenter to Binta's father. Binta's brother is a tailor. (*12) On occasions, he assists Coto Jaila by "minding" his table. I recall that one morning, Momadu Bailor [ii] decided that he would accompany Coto Jaila wood-collecting, much to the latter's amusement. Unable to carry anything like the same amount of wood as Coto Jaila, Momadu had nonetheless fallen over three or four times during the tricky descent down the steep forest path into town. iv. Movement and mobility: A digression. I have already indicated some of the ways by which Fula traders, from Futa Jallon, have come to settle in Kabala. However, it should be stressed that for many, the journey has not ended here. Many Fula, recently arrived immigrants will, no doubt, follow the well-established pattern of moving on elsewhere if the local prospects do not look good. But, as I was to discover, even for the twenty to thirty year old Fula man or woman, born and raised in Kabala, movement to another town, another region, or even another country, remains a distinct possibility. Mobility is, as it were, a part of the cultural heritage and a part of the social repertoire of the Fula in Kabala. As Haja explained, "Fula man, i de walka no mo" [Kr.], which literally translated, comes out as "Fula do nothing but walk". (*13) I was told that wherever I cared to travel, I would meet Fula. Senegal, Mali, Cameroon, Nigeria, Sudan and even Ethiopia, were mentioned among others, as countries where Fula were "known" to have settled. It was generally understood that Fula were known by different names in different parts of the world. The "Fulani", for example, were recognised by informants as being the same people. One of Haja's relatives from Makeni, a highly educated and widely travelled man, spoke of the Fula as "the Chinese of Africa", and the "Black Chinese", whilst another informant referred to the Fula as "The Jews of West Africa".(*14) I was surprised by the knowledge many of my acquaintances had of other regions and of other countries; although I accept that a good deal of what I was told was hearsay, usually anecdotal, and at times dubiously accurate. Nonetheless, I also discovered many instances of family networks that crossed a number of international |

|

65 |

|

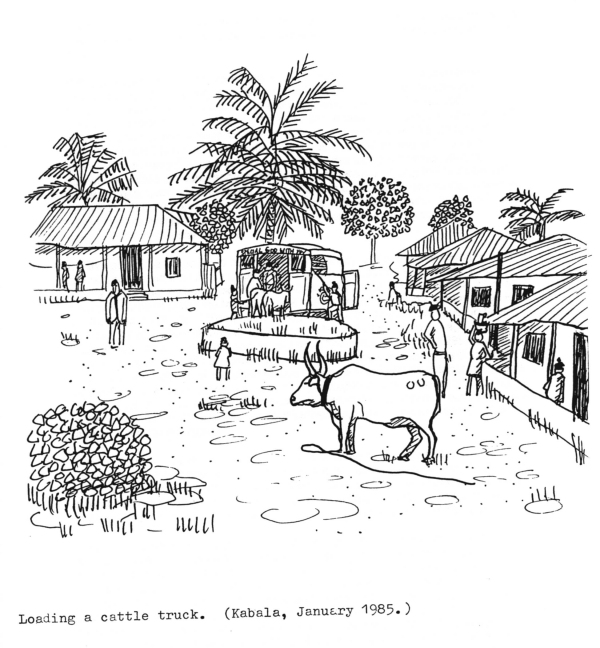

ILLUSTRATION 4:1 |

|

| borders, and not merely that between Sierra Leone and Guinea. The wide dispersal of family members appears to be

a notable feature of local Fula social organisation. (*15) The high degree of mobility exhibited by the Fula is a multi-faceted phenomenon. It cannot be explained simply by a "scratch a Fula and discover a transhumant pastoralist and/or itinerant trader" type of argument. (See den Ouden 1987) However, despite its many aspects, I believe that mobility is a factor of central, and possibly unifying, importance for Fula in Kabala and elsewhere. In particular, the freedom of mobility reflects something of the self-confidence and self-esteem expressed by many Fula individuals. The awareness that possibilities may lie elsewhere, reflect an assuredness that is perhaps lacking among the "indigenous" ethnic groups. Such assertiveness is, I feel, based on cultural experience. In Sierra Leone, the Fula are prosperous, and wide social networks, a legacy from the long history of Fula immigration and dispersal throughout the region, facilitate geographical and social mobility. On this point, there appear to be a number of striking similarities between the Fula of Sierra Leone, and the Hausa traders of Yorubaland, described by Cohen almost twenty years ago. Cohen observed that the Hausa control of long distance trade in Kola and cattle required the formation of a network of highly stable communities in the towns and villages of Yorubaland. This, he argued, "involved various kinds of mobility of population through which demographic adjustments in the age, sex, and occupational structures of the community have been made" (1969, p.29) Hausa economic organisation is described as being "at the basis of a far flung diaspora", consisting of a network of localised Hausa communities, formally established on the basis of Hausa cultural distinctiveness. "These customs, which are far from being a replica of northern Hausa culture, provide a stable institutional set-up which facilitates mobility and makes the establishment of further outposts of Hausa trade possible." (ibid. p.9; emphasis added) Cohen assumes, rather than demonstrates, that there is a link between Hausa commercial success and mobility. Although the subject is not dealt with in any great detail, it is an obvious point, and one that finds support from my own data. However, it should also be recognised that just as mobility creates wealth, wealth facilitates mobility, and in the notes that follow I hope to show the relevance of this point. I begin with what may be called the economics of mobility. Fula involvement in trade both entails and encourages a good deal of mobility. Fula traders, as I have indicated, are generally flexible in their business practices, and many show a willingness to experiment, not merely in different market outlets, but also with a number of products. Even among the established wealthy traders, total specialisation is uncommon. Furthermore, it should also be recognised that trade, in itself, frequently necessitates mobility. Along the entire marketing chain, from wholesalers through middle-men, such as Mr.Jeng, to the final retailers, like Coto Jaila, goods are distributed and then redistributed. The journey may be as long as six hundred miles or as short as six hundred yards, but at every stage redistribution is facilitated by the movement of people. The Fula do not dominate the border trade between Sierra Leone and Guinea, however they are much involved in this field of commerce. Furthermore, the cattle trade across the Guinea-Sierra Leone border, and within Sierra Leone, is almost |

|

66 |

| exclusively in the hands of the Fula. I discuss the cattle trade in further detail below. However, by now it should

be clear that a large number of the Fula elders in Kabala have large cattle herds of their own. There are also

close links between these urban Fula cattle traders, and the rural "traditional" Fula cattle herders

and owners. The cattle trade is international in its operations, and livestock are frequently taken from Guinea via Sierra Leone on to Liberia. I am certain that cattle trading is the single most important source of income for the Fula community in Yogomaia, if not in Kabala. (see above) However, whilst large numbers of cattle are herded locally, many cattle are drawn from Guinean herds. Furthermore, the major markets for beef are distant from Kabala. Traders, and other people involved in the cattle business, have to undertake long journeys away from home. It is common for a trader to spend three or four weeks on a trip from Kabala to Monrovia. By contrast, women's economic activities, are usually carried out nearer to home. (See above) Movement and mobility of women are, to an extent, a "function" of marriage, (cf. Stenning 1966 p.110-11) and a logical result of the pattern of male migration. The example of Coto Jaila provides a literal demonstration of the Fula adage, that "a man should go before". In most instances a woman is expected to join her husband upon marriage. This usually involves her removal from her natal residence, to that of her husband. (*16) In some instances, marriages are transacted over very long distances, as the "family marriages" on the kinship diagrams relating to Alhaji Pita (diagram 4:1.) and Mr. Jeng (diagram 4:3.) show. Even when the marriage has been transacted locally, migration by the husband will frequently entail the separation of the wife from her "own" family, as happened in Coto Jaila's first marriage. However, despite the long distances which may be involved, return visits are made on a number of pretexts. These ensure that women are able to keep in contact with their natal kin. For example, most women will seek to visit "home" in the event of a wedding or death involving a close family member and it is the common practice for pregnant women to return to their natal home to give birth, especially to a first child. (*17) A woman may well retain a range of property rights and interests that continue to involve her with her own kinsmen. For example, it is not uncommon for women to own a few cattle. Cattle given to a bride by her husband upon marriage are kept as a part of the husband's herd. But cattle a woman may have inherited from her own family, are frequently left with her own kinsmen: Although she may take to her husband cattle donated by her family as part of the marriage prestations. Maintenance of property rights inevitably requires a show of interest in that property. Accordingly, a woman is wise to make periodic visits to assess the health and general condition of her cattle, if she is to prevent them from being "eaten" by her kinsmen.(*18) It might be assumed that in old age, men and women become less mobile (*19). In general this is true, but for many men, and for a few of the wealthier women, age and elderhood bring with them the prospect of embarking upon Hajj which, for most, will be the longest journey they ever make. There is something paradoxical about the Hajj. On the one hand, the obligation to perform the pilgrimage is an integral part of the Islamic tradition. On the other hand, fulfilment of this traditional obligation, takes the pilgrim far away from his or her home: the familiar social environment in which the "traditions" of everyday life are acted out. |

|

67 |

| Haja made the Hajj twice. She professed a religious faith that was assured in its simplicity. "Everything

is God", she would say in response to my questions concerning various charms and potions that I came across.

By so doing she formally denied their efficacy. And witches? "That's foolishness, nothing more", she

told me. In public, Haja expressed little faith in most manifestations of local belief systems. Haja never gave me a detailed step by step account of where she visited or what she did on the Hajj, and I gathered that the religious ritual aspect of her visit was bewildering to her. She preferred instead to show me her set of three-dimensional colour transparencies which depicted the various stages of the Hajj, that she had purchased on her last visit. Her own reminiscences were like those of any tourist (*20). They concerned the local style of dress, the food, and of course, the weather. Fragmentary though her own observations were, I believe that the collective experience of the Middle East, gained by the Fula through the Hajj, must be significant in shaping community attitudes. The Hajj provides, as it were, a window to the world and gives older Fula the opportunity to experience, albeit in a limited fashion, an alien culture. By contrast, for younger Fula at secondary school in Kabala, western education is seen to offer something more. Success at school is thought to bring with it many exciting possibilities, and not least among these is the chance to travel overseas, usually to the United States or to Britain.(*21) I suggest, however, that the attraction of these "western" countries is more than just a desire to see other people; it involves, more often, a desire to become other people. Inevitably, this has entailed a clash of values between many children and their parents. Many schoolchildren's aspirations are impracticably high (*22) and whilst the pursuit of a secondary education often entails movement from one town to another, only a very small percentage of students ever gain the opportunity to study overseas. (*23) On the other hand, considering the size and the remoteness of Kabala, a surprising number of Fula had travelled abroad. (And when I take into account the other Fula "known" to my informants to be studying in the United States, "London", or "White Man's Country", I can only adduce that a considerable number of Fula are abroad.) At least seven local children from among the wealthier Fula families had studied, or were presently studying, in the United States or in Europe. Not surprisingly, the progress, or otherwise, of these particular children excited considerable interest. In the parlour of Haja's house, there hung a number of photographs. Three were traditional, stern-faced portraits; these were of Haja Aisaitu, Alimamy A.R.Jalloh, and Abu Jalloh, the latter's kinsman. The remaining two photographs were very different in style, both from each other, and from the previous portraits. One showed a young and evidently happy couple. In the photo a smiling man stood with his arm affectionately around the waist of his attractive companion. The couple were in America. The man, Mohamad Barrie, was born in Manan, a small Fula settlement approximately seven miles north of Kabala. He had been educated in Kabala and in Freetown, where he married. From Freetown, Mohamad Barrie had gone to America, accompanied by his Fula wife. The other photograph, at first glance, appeared to be of a ship; a tanker of some description. But on closer examination, superimposed in one of the corners was the |

|

68 |

| blurred image of a young man's face, the son of Haja's brother, Alhaji Momadu Bah. The youth had left home during

the mid-1970's, to go to Freetown, where he found employment on a ship. He returned for a brief visit after two

years abroad, but has not been heard of since that time. Sadly, the case of Alhaji Mamadu's son is not unique, and many older Fula, Haja among them, voiced disquiet concerning their children's desire to visit America or Europe. Some parents with children overseas had not heard from them in years; for others, the return visit of their children had brought only shame and embarrassment to the family. (*24) One Kabala youth was, allegedly, deported from Germany back to Sierra Leone. I was also told the story of a man who revisited Kabala after spending several years in the United States. Evidently he brought nothing for his family, except some medicine. I do not know how long the man stayed, but, as he was leaving, he discovered that he had left a belt inside the house. Unable to discover the belt's whereabouts, he accused the children in the house of its theft. I was told that the man's father, a respected elder, was so angered, that he laid blows upon his son for daring to curse the family he had not seen in such a long time. More tragic, is the case of Alhaji Boie's own son, who had gone to the United States to study. The youth died under very unfortunate circumstances. Alhaji Boie paid to have the body of his son flown back to Sierra Leone and brought to Kabala. The empty coffin now resides at the back of the Yogomaia Mosque, a permanent reminder of the lamentable event. One young man, who expressed a desire to go to the United States himself, commented sardonically on how the tragedy had made many people worry about letting their children go abroad to study. He observed that it cost a lot of money to educate one's children simply to face the added expense of having them buried. Although Fula remain keen to have their children educated at school, some parents spoke of the need to limit or redefine their children's expectations.(*25) This was an issue that affected Haja's own household. Kindi frequently complained to me that his plans to go to America were being thwarted by Haja's intransigence. By his reckoning, the sale of three or four cows would have provided him with sufficient money to make the journey. (Kindi claimed that at least this number of cattle were owing to him as part of his inheritance from his father, whose cattle had been kept alongside Haja's own herd.) I once raised his "case" with Haja, but she remained totally opposed to his going abroad, and refused to provide him with any money for this purpose. As far as she was concerned with "schooling" it was possible to get good jobs in Sierra Leone. Haja emphasised that in giving to one's children one gave something of oneself. "It was not right that they should just leave. Besides," she argued, "Kindi has a mother, let her pay for his fare. Not that she ever would!" Haja's reluctance to encourage her dependants to leave her household is understandable. (See above) But as she readily admitted on other occasions, "Fula do nothing but walk". I have suggested that there is a close link between commercial success and mobility. This is also recognised by many Fula. I once asked Coto Jaila why the Fula were so successful in trade and business. First he drew my attention to the long history of the salt and kola trade. "Sons will follow their fathers", he said, "as the skills of the fathers are learnt by the sons". He thought for a moment, then added:-" Once you have left your home, you have left the security of your family. You go somewhere where you are a stranger. You will do any sort of work, and can live in any conditions because |

|

69 |

| you will not shame. You will try anything to make money. Also, you do not have the same family demands on your resources- no younger brothers. This is why it is difficult for a Kuranko to trade around Kabala. His relatives will come and stay, and beg. But Kuranko don't walk much anyway. All they really know about is farming." |

|

70 |