|

|

| In addition to his wives and offspring, a fourth hut was occupied by Tela, full sister of Jiba, Wurie Juwe's mother.(*4)

During my research, Jiba spent a great deal of her time at Haja's house in Yogomaia. (See above.) Jiba, in marked

contrast to her son, exploited her lowly status to good effect. By taking on the role of "dependant",

Jiba ensured that Haja was not in a position to withdraw her patronage. At the warri, Jiba resided with her sister.

Both women were widowed but, as is customary, had remarried. Jiba had been "inherited" by Chernor Wurie,

whilst Tela's poor, indeed, I believe quite destitute husband lived elsewhere, and had little or no contact with

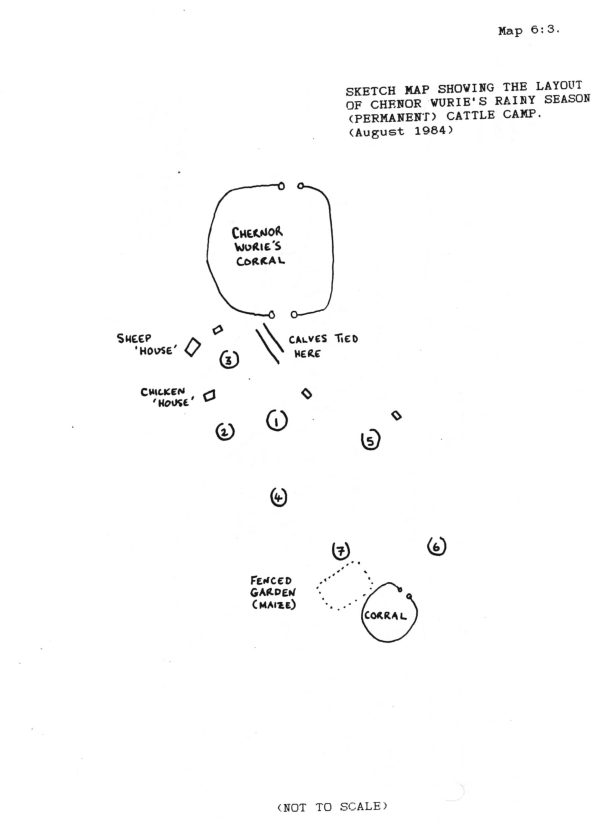

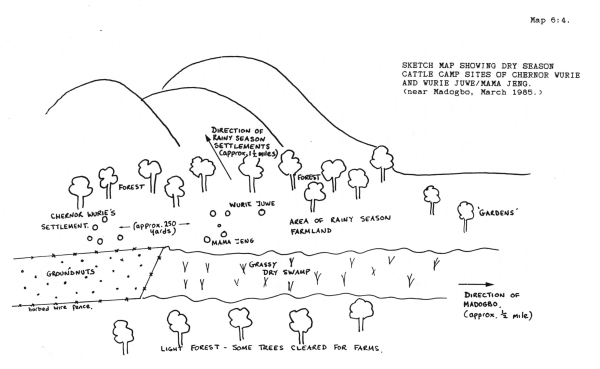

the warri. Mama Jeng, of similar age to Wurie Juwe, was a hired herdsman. He was a Tellico Fula, and had worked previously at one of the five warris owned by Alimamy Jalloh, the former Fula district headman. Following Alimamy Jalloh's death, the warri where Mama Jeng had worked was disbanded. Haja told me that she had taken on her husband's former employee out of "sorriness". Mama Jeng, who owned but a small number of cattle, was visibly poorer than Wurie Juwe. Mama Jeng lived in house five, along with his wife, his eldest son, aged around thirteen years, and two younger daughters. Another son had been sent to a Koranic teacher at one of Alhaji Boie's warris, situated a mile or so away. Chernor Wurie: "Kaseya". Chernor Wurie's warri, known locally as Kaseya, lay ten minutes walk from Wurie Juwe/Mama Jeng. Similarly situated on a level clearing among the wooded hill slopes, this settlement was also made up of two family units. (see map 5:3) Chernor Wurie was Haja's matrilateral cousin and, it was also suggested, a distant patrilineal relative. Chernor Wurie, in his mid-fifties, had spent his life in the warri, although his house in Yogomaia, built over a number of years was, at the time of my visit, nearing completion. (see above). Chernor Wurie's own herd numbered over one hundred and thirty head of cattle. (*5) He had formerly herded his cattle along with those belonging to Haja but some years back, had formed his own warri, when the joint herd had become too large. (See below) Chernor Wurie still took an active interest in Haja's herd and was, from time to time, involved in important herd-management decisions. But on a day to day basis, his chief responsibility lay with his own herd. Chernor Wurie had three wives in the warri, (houses one, two and three). Chernor Mariama, the senior wife, had borne seven children to Chernor Wurie. The eldest son, Chernor, who was married, lived in house five along with his wife and first born. (*6) A married daughter, Lama, also lived at the warri, accompanied by her husband and three children (house four). One other married daughter lived with her husband at Gbindi, a market town on the Guinea-Sierra Leone border. Her surviving children lived at the warri. Chernor Habe lived with her ten-year-old grandchild, daughter of her only son Alpha, borne in a previous marriage. She had been married to Chernor Wurie for many years, but had not conceived again. An unmarried Tellico hunter, in his early twenties, also resided with Chernor Habe. Some kind of agreement had been made between this man's father and Chernor Wurie and, although the details were not |

|

96 |

|

MAP 6:3 |

|

|

|

MAP 6:4 |

|

|

| made known to me, the length of time this man had been with Chernor Habe, ten years or so, suggests that he had

been "adopted". (See above) Lama, the third wife, (house three) had two young sons, both under five years. I think she was of slave origin. Chernor Wurie also had a young bride in Kabala, where she lived in a rented room. This woman, a Futa Fula, had been married previously. She bore her first child to Chernor Wurie, during my stay. This wife engaged in some petty trading in town, and was not involved in the day to day affairs of the warri. The other herding unit consisted of Chernor Barrie and his wife, their unmarried daughter (house six), their married son and his wife (house seven). Chernor Barrie had no more than twenty cattle, but these were penned separately. This family, who were not related, had co-resided with Chernor Wurie at a previous site at Yataia, near Kabala. Chernor Barrie had accompanied Chernor Wurie to Madogbo for, it was suggested, protection. (*7) iii. Madogbo: Seasonal movements and warri mobility. (*8) During the 1984-1985 dry season, both Wurie Juwe/Mama Jeng and Chernor Wurie moved eastwards to camp alongside the edge of the Madogbo watercourse. The two units, situated approximately 250 yards apart, remained here for three or four months, between January and April, before returning at the start of the rains. (See sketch maps 5:1 and 5:4.) The distance between the rainy season sites of Kasoto and Kaseya and the dry season site at Madogbo was not far; approximately one and a half miles. Nonetheless, the move entailed an important change of "scenery", as the camps were transferred down from the wooded and sparsely cultivated savannah hillslopes, to a valley area of more intense cultivation. Fula herder residence patterns commonly entail an upland-lowland seasonal movement, spoken of by Fula themselves in "up-and-down" terms. (*9) In many instances the distances between the dry season camps and the more permanent rainy season sites are very short indeed, often under a mile. Furthermore, when distances involved are small, certain family members might stay behind to look after the rainy season camp. (*10) Generally speaking, as the data presented indicates, the pattern of transhumance is, in terms of distance, very limited, indeed, the terrain and vegetation of the region is not suitable for the movement of cattle over longer distances. (*11) Nonetheless, the seasonal transfer is regarded by the herders as essential to give them access to dry season pasture and water, for use by both the cattle and human populations. (*12) The move to Madogbo brought the Fula families and their herds into close proximity with the Yalunka farmers. However, by this time, most of the crops had been harvested, save for a few "gardens" situated near to the farming settlements. (But see below) Agreements had been made between the Chenor Wurie and Wurie Juwe on the one hand, and the local farmers on the other, to allow the cattle to graze upon the stubble of the rice swamp, and upon the numerous unfenced farm plots found throughout the lower part of the valley. (Further details on herd management follow below.) Relations between Chernor Wurie and Wurie Juwe, both of whom had lived |

|

97 |

| in the area for a number of years, and the local farming community appeared to be cordial, and involved a certain

amount of cooperation. (*13) The Fula cannot be regarded as truly transhumant, let alone as nomadic. The construction of rainy season settlements (rumirrgol F.) requires a large input of human labour. The houses are permanent structures, and may stand for ten years or more, although the reed roofs must needs be replaced every three or four years and repaired annually. These houses are called sudu; by which town houses are also known. By contrast dry season settlements (se'dingol F.) are marked by their temporary houses (tipuru F.) which are used for one season only. Similarly, the sturdy fenced corral (hu'go F.), in which the cattle are penned nightly during the rainy season, is not a feature of the dry season settlements. Although many of them are immigrants, some Fula herders I visited had remained on one rainy season site for thirty years or more, (although this family had utilised a number of dry season sites). In other cases families had moved, but a few hundred yards to somewhere "clean". So although the Fula herders in the region may not have settled in the general sense of their being and feeling secure, it is not incorrect to say that Fula can and do settle. (*14) Yet movement always remains a possibility, and I learnt of many reasons for moving. Among them: to seek better pasture; for cattle health reasons, e.g. I was told that cattle which had remained in an area for a long time were more prone to certain diseases; to avoid cattle theft- this was a particular problem around Kabala; to avoid loss of cattle- I was told that cattle which remained in an area over a period of years became difficult to herd because they became too knowledgeable of the terrain and could hide easily; to move closer to relatives and friends, or to move away from relatives and enemies; to move closer to town; to move further away from farming settlements, e.g. if cattle damage to crops was a particular problem. And so on. As mentioned previously, both Chernor Wurie and Wurie Juwe had formerly been encamped near Yataia, an area approximately five miles south of Madogbo. The move to Madogobo, it appears, had been prompted by grazing pressure and the need to divide the herding unit, which had formerly consisted of Haja's cattle and those of Chernor Wurie. The two newly formed units had been at Madogbo for four years by the time of my research. Warri movements made by Chernor Wurie and Wurie Juwe over the years reflect what is, essentially, an opportunistic strategy which clearly relates to the fact that Fula herders have no formal rights in the land on which their cattle graze. (*15) When a herd-owner plans to transfer his herd, he will consult with the local paramount chief and seek his approval and, possibly, assistance in the selection of a new site. The herder may present the chief with a gift of "Kola", (money or, perhaps, livestock) to show respect, but there is no fixed rental agreement. The chief can expect to benefit in a number of ways; he will receive a greater share of head taxes collected, by having a greater population within his chiefdom. He also stands to gain from having a reservoir of livestock from which he will expect a gift of cattle, goat or sheep, for an important religious or other ceremonial occasion. But money may be given on other occasions. Haja Fatmata, Haja Aisaitu's co-wife, told me that she often gave money to the paramount chief on the sale of a cow; the money was presented saying, "here is your small cow". In 1983, the Limba section chief had many children from his locality to be circumcised and asked the local Fula to |

|

98 |

| contribute to the cost; Haja Fatmata gave a one year old cow. Haja Fatmata referred to these payments as "tribute"

(in English), and said that contributions of this kind were expected to 'help' if 'trouble' occurred at a later

date. (*16) There was some uncertainty whether, at the end of the 1985 dry season, Chernor Wurie would return to Kaseya, or move towards Bafodea. A number of options remained open. Rainy season grazing and browse were not in short supply, however, agricultural extension work in Madogbo had affected the availability of dry season pasture. A large area of the Madogbo swamp had recently been secured with a barbed wire fence, supplied, I presume, by the Koinadugu Integrated Agricultural Development Project. Behind the wire grew a dry season crop of groundnuts. (I shall return to this 'development' issue below.) But this was not the only factor that Chernor Wurie had to consider. Firstly, cattle theft in the area was on the increase, and he had "lost" four adult cows during the previous year. (And see above.) He believed thieves would be less of a problem towards Bafodea. Chernor Wurie was also concerned at the recent outbreaks of cattle sickness, apparently Black Quarter (koingal F.), in the surrounding warris. Finally, and this may have been the most "unsettling" factor, I believe that Chernor Wurie was being pressurised to move out of the area by Alhaji Boie, Haja's husband, who wished to use the vacated pastures for his own very extensive herds. (*17) The transfer to new sites over long distances does occur, and, for example, a large number of Fula herders from the Yalunka chiefdoms fled to Warra Warra Bafodea, a Limba chiefdom, to escape from the inter-ethnic Fula-Yalunka fighting which erupted following the abortive 1982 general elections. (*18) Nonetheless, I believe that the shorter move, as exemplified by Chernor Wurie, is more typical, reflecting, perhaps, a process of continuing adjustment to a range of ever-changing local conditions. Whilst social change is as constant as the passing of time, it should be remembered that Fula herders are still migrating into the area and, it may be argued, moving to exploit a new niche. (*19) In many respects the herders in the region may be seen as pioneers, the constant changes in residence merely one aspect of the experimental character of a pioneer society. iv. Milk and the market; the productive labour of women. Women usually milk the cattle; a task carried out shortly after dawn each morning. (*20) Milking begins as the calves, tethered during the night, are released, one by one, to find their mothers who have spent the night in, or around the corral. After the calf has suckled for a few seconds, and the mother has started to drop her milk, the calf is pushed, prodded or led aside whilst the woman, crouched or sat upon a small stool, milks. After a few minutes, if the milk dries up, despite patting and stroking, the calf is allowed to return, and the procedure is repeated until the cow is fully milked. It takes about five minutes to milk each cow. (*21) Milking is a task associated with married, rather than unmarried women, although elder daughters do help out. A woman will milk the same cows each and every day, and the milk which is collected in a large calabash, is taken back to her own house, and not mixed with that of other women in the warri. This milk is regarded as the |

|

99 |

| woman's property, and whilst its distribution and processing is governed by social custom, (and hence the husband

and other "dependants" may make claim to the milk), it is the woman who is responsible for these basic

tasks. Milking thus reflects, and more positively, defines smaller sub-structures within the herding unit, around

which many of the day to day domestic tasks are organised. But more than this, it is only with reference to these

sub-structures that many of the longer term processes relating, for instance, to inheritance and herd division

can be understood. The women are very much at the centre of things. At Chernor Wurie's warri there were five milking units (excluding from this particular discussion the associated herding unit headed by Chernor Barrie). Chernor Wurie's three wives formed three of the units, with his married daughter, and the daughter-in-law, forming the other two. A woman may come with cattle upon her marriage.(*22) And it is customary, if resources permit, for a husband to give his bride a cow upon marriage. These cattle are regarded as a woman's own property, but the rest remain the property of the husband. Nonetheless, from the remaining herd, the husband allocates to each wife, a number of cattle to milk. These usufructuary rights are not inalienable, and a husband will reallocate these cattle upon subsequent marriages, according to the number of dependants each wife has to feed and, of course, according to the growth of the herd itself. Notions of equity are thus contingent upon the particular familial requirements of each sub-unit. After the cattle have been milked, they are released from the corral and driven by the man away from the camp. The women, with the help of their daughters and other young children, then clear away the cow dung from the corral (it may be used as a fertiliser, but not necessarily). Apart from tending to any sick animals, and the care of younger calves, kept at the camp until old enough to wander on their own, the cattle play no part in the daily round of domestic chores until the following morning. It is the women, rather than the men, who "care" for cattle. Over the months and years close attachments are formed between the wife and the cows she milks. I observed that cows would sometimes make their way to their milker, and stand patiently until attended to. Not surprisingly, it is often the women who first notice injury or illness within the herd. The amount of milk a particular cow is producing, for instance, will not come to the husband's attention unless he is told, although he will take the opportunity to cast a critical eye throughout the whole herd each morning before the cattle are driven to pasture. (*23) From my observations I gathered that this aspect of women's labour was fairly standardised, although the size of the camps, both in terms of human and cattle populations, affected how much time was spent with the herd. In addition, during the rainy season, most women engage in some form of agricultural production. At Chernor Wurie's warri all the wives had made small, securely fenced, farms near to the encampment. Upland varieties of rice, and maize (kaaba F.) seemed to be the most common crops, although fundi, or hungry millet, (funye F.) was also grown. I got the impression that the development of these farms is very much an individual activity. Hired labour, often non-Fula, may be used to prepare the ground, and I gathered that sons will help their mothers, and co-wives may co-operate in a number of tasks related to these fields. Nevertheless, the produce is not collectively "owned". As with the milk, the harvest is taken by the women, back to their own houses, where |

|

100 |