|

|

| CHAPTER SEVEN COWS AND COWBOYS: THE COMMERCIALISATION OF CATTLE PRODUCTION |

| Fula herders are not subsistence farmers. They are specialists in cattle husbandry. In this chapter I shall try

to show what effect the growing demand for meat has had on some aspects of Fula husbandry and herd ownership. I shall also discuss how trade in livestock is carried out, so that the position of the Fula herder within the structure of the economy can be understood. |

|

117 |

| i. Introduction; commercialisation of cattle production. When I was green in the field I naively said to Coto Timbi, a neighbour and cattle trader, that I supposed people who lived in the "bush" had little need of money. His response was immediate and to the point. "Mr. Brima, wherever you are, whether you are in the 'bush' or in the town, you need money. That is how the country is now. All men are used to 'eating' money". Fula herders are not subsistence pastoralists, and it appears unlikely, certainly within Sierra Leone, that they ever have been.(*1) They are specialists in cattle husbandry and as such have necessarily been dependent on the "market" for a range of foodstuffs, in particular rice. (*2) Fula sell milk (*3) and cattle. Sale of cattle used to be seasonal; stock was sold/exchanged for grain at harvest time. But such a simple relationship no longer exists. (*4) Fula herders are not simply consumers of rice or other agricultural produce; they all consume a very wide range of manufactured items, most of which emanate from the "first" and "second-world", but which have been made available locally through the "international market economy". As "consumers", Fula herders are increasingly dependent on the market for which they produce beef and milk. The degree of "market integration" is difficult to assess, especially in quantitative terms. (*5) I shall try to show what effect the growing demand for meat has had on some aspects of Fula husbandry and herd ownership. Firstly, I shall compare cattle husbandry practices in Sierra Leone with those reported to occur in Guinea. Secondly, I shall contrast "traditional" with "modern" herd ownership patterns, and examine briefly how cattle ownership rights are changing. It would be misleading to explain the differences between Fula herding practices in Guinea and those in Sierra Leone simply in terms of lesser or greater integration into a market economy; obviously a wide range of factors are involved. For instance, in Guinea, ownership of cattle is less concentrated in the hands of Fula, and I was told that many more people owned cattle, but each owned fewer of them. The uphill-downhill pattern of transhumance, which is a feature of Sierra Leone cattle husbandry is less common in Guinea where cattle are more commonly herded around settlements throughout the year. I was told that unused bush and grazing land was scarce. So herd expansion was difficult; hence the attraction of Sierra Leone for so many cattle herders. I was told that some families were likely to remain in the same place for many generations, so one or two "families" would often dominate a whole town, or area. Fula in Guinea are not "strangers", and rights to land are conferred in both national and customary law. (*6) Informants, when characterising the differences between themselves and their northern kin, mentioned that Fula in Sierra Leone were more directly involved in the market economy, and especially the market for meat. As Coto Jaila commented "people follow money". If you had the money, he explained, you would come and live in Yogomaia, amongst strangers. By contrast, in Guinea there is tawi tawi, inheritance or continuity, and a son follows his father and grandfather in their trade or profession. |

|

118 |

| A number of herders commented that herds in Sierra Leone tended to be much larger than those in Guinea. Such a

comment could mean one of two things, and on enquiry often meant both. Firstly that herding units tended to be

larger in Sierra Leone, and secondly, that the numbers of cattle owned by any one individual were frequently higher

than could be expected of a person of similar rank or status in Guinea. One important consequence of the "increase"

in herd size is that cattle in Sierra Leonean herds are regarded as being difficult to manage. (*7) In Guinea,

the Fula have a closer relationship with their cattle. Cows are individually named, are much more used to human

contact, and can be expected to return to the cattle camp of their own accord. The Fula I met all seemed to believe

that a move to larger herds, diminished intimacy with the animals, and closer involvement in the market (especially

in the meat trade) all went with movement from Guinea to Sierra Leone. So that if we accept market as 'modern',

and subsistence milk pastoralism as more 'traditional'- then the physical move to Sierra Leone by migrants paralleled

a movement in time from 'traditional' to 'modern'. Cattle, as property, then, may be seen to be changing, namely from socialised domestic animals with familiar even personal relationships with their human herders, to creatures regarded more simply as objects with a market value. From my observations, and comparative sources (Stenning, Dupire, Hopen etc.), Fula cattle have never been the "focus of a wide range of claims" so familiar among East African pastoral societies. However this does not mean that ownership or rights in cattle are always unambiguous. (*8) In many camps I visited, the cattle had originated from a number of sources. Cattle that a man had inherited from his father or other male kinsman, cattle that accompanied the herd owner's wife or wives, cattle that the herder was minding for kinsmen, who were perhaps not involved in herding themselves, and often cattle that were being looked after for non-kinsmen on a purely commercial basis. Many of the cattle most clearly "belonging" to the herd owner would also be the objects of a variety of rights held by his near kin. For example, in addition to the cattle that women bring with them upon marriage, it is customary for the husband to provide his wife with one or more cows from his own herd. These cattle and their offspring are, in customary law, the wife's property. A husband shall also provide his wife with cattle to milk, which remain the property of the husband, but the milk and the various milk products are regarded as belonging to the wife, for her to distribute and dispose. A man's sons and even daughters may also claim a variety of rights in the herd. A child should be presented upon birth, a cow in his or her name. Theoretically, this gift holds "the promise of a herd", as the subsequent offspring are the child's property. So whilst cattle, in this instance, are not "mobile bundles of rights", ownership is seldom "single-stranded". (*9) By contrast in the camps of the wealthy cattle traders, rights in stock were much more clearly defined. (*10) The herders were often hired hands, but they also drank the milk of the cows. One or two "big men" admitted a preference for employing non-kin who cannot legitimately make further claims on the owner or his property, although many wealthy herd owners were prepared to employ their own kinsmen as herders. In general, cattle of Futa traders, such as Alhaji Boie and Alhaji Pita, were perceived to have "come from their own efforts", and were thus regarded as theirs alone. (*11) |

|

119 |

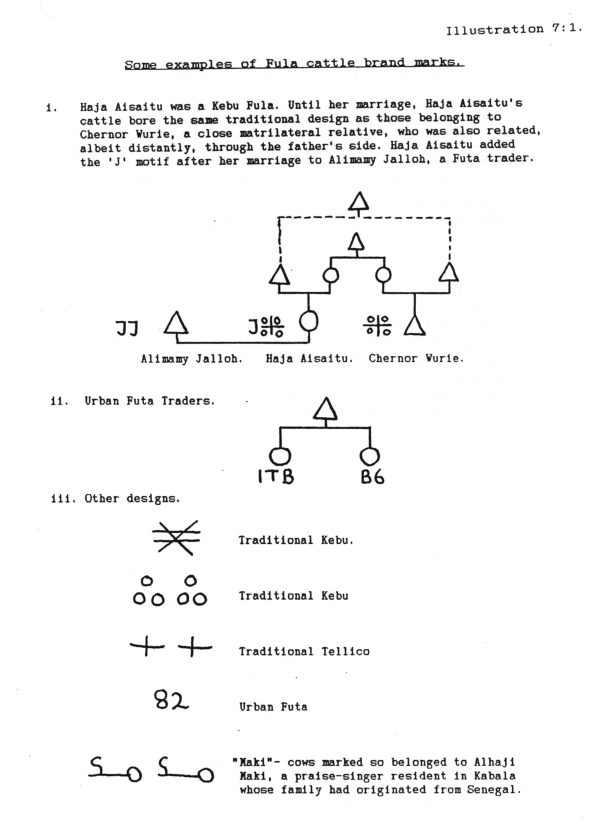

| The marking or branding of cattle for identification suggests that the half-perceived trend towards individualised

ownership of cattle is a permanent change. At around one year of age, when the hide is tough enough, cattle are

branded. Traditionally these brands are of simple geometric design, consisting, for example, of a cross, or a number

of circles or parallel lines. These designs are passed down from human generation to human generation, often with

little alteration. Cattle can thus be identified by insiders as well as outsiders as "belonging" to a

group or, depending on the design, a category of people much larger than a simple domestic unit. This does not

mean that property rights are confused, in the sense that ownership of each beast is not individually recognised.

Traditionally, the markings on cattle belonging to siblings or cousins would vary only slightly if at all. But

urban cattle owners mark their own property unambiguously, often with individualised brand-marks; for example,

with a series of numbers or their own initials. I noted instances from trading families where the brand marks of

full siblings bore no relation to each other at all. (See diagram 7:1.) . In Sierra Leone cattle are a marketable commodity. Cattle markets in Guinea form an important part of the cattle trade network, but the centre is based in Sierra Leone. It appears that there are less opportunities to trade in cattle in Guinea than in Sierra Leone where cattle trade profits are transferred to other trade and business ventures and are used instrumentally for market investment. This has far reaching consequences. I was told that in Guinea when cattle had to be sold to buy rice, much care would be taken to maintain the balanced composition of the herd. To this end, it was usual to cull only old cows and mature steers and replace them with young stock. I was told that in Guinea, chickens and smallstock were valued in relation to cattle and, for example, that smallstock could be sold to replace the loss of a cow. My informant provided the following valuation. 8 fowl = 1 goat 7 goats = 1 cow 5 sheep = 1 cow I do not think that this replacement strategy is so widely utilised by Fula in Sierra Leone. (*12) As one informant explained, this is why warris are often "used up", in Sierra Leone. Cattle sold for family needs, such as household expenditure, were not necessarily replaced, and instances were recalled where men, invariably Futa traders, had sold off their entire herds to move into other business ventures. ii. "Cow boys" and Toyota Trucks: Livestock trading. The increasing involvement of Fula herders in the market economy has been stimulated by a number of factors. Not least among these has been the alluring presence of foreign manufactured items in the local markets, which blur the distinction between human wants and human needs: The want of a transistor radio inevitably involves the need of batteries to play it. Cigarettes become addictive; and plastic sandals, once a luxury for stone-hardened soles, become a necessity for feet used to their protection. The exchange of cattle, the herders' main resource, for these and like commodities, has been made possible by the market demand for meat, not just locally, or nationally, but internationally. However, demand alone does not |

|

Illustration 7:1 |

|

Some examples of Fula cattle brand marks. |

|

| ensure supply, and I shall examine how trade in livestock is carried out, so that the position of the Fula herder

within the structure of the economy can be understood. I begin with some general points about Fula involvement in the cattle trade. Fula dominate the livestock trade within Sierra Leone; a fact which has been the cause of much governmental and popular concern. ( See below.) It is clear that Fula success in trade, and their dominance of the livestock trade in particular, whilst currently reflected in their ownership of large herds of cattle, did not initially rest upon this but rather upon access to the extensive herds of their co-linguists, (the Kebu, Tellico and Hubu, both within Sierra Leone and Guinea) which allowed them to respond to the new market opportunities. The establishment of an indigenous livestock industry within Sierra Leone, then, was the result of a coalition of sorts between two sections of Fula society; on the one hand the Fula herders, and the Fula traders on the other. As I have shown, divisions within the Fula community persist, although sub-group identities have blurred somewhat as Fula have found themselves labelled as "strangers", and largely excluded from Sierra Leone's developing national identity. Throughout this study I have found it useful to distinguish between Futa traders and "traditional" cattle herders, and in the present context, it is more accurate to say that it is the Futa Fula who dominate the cattle trade. However, just as many Futa traders have become herd-owners, increasingly Fula from traditional herding sub-groups now trade in cattle. (*13) One of the wealthiest cattle traders in Kabala was, in fact, of Kebu birth. In the discussions that follow, I shall continue to write in terms of trader and herder, but it should be borne in mind that these occupational categories are not mutually exclusive, and do not necessarily relate to sub-group identities. Coto Timbi, a cattle trader. Coto Timbi, who was around fifty years old, lived next door to Haja. He was a cattle trader, a former employee of the late Alimamy Jalloh, but now worked for himself. He was born in Timbi, a large town in Futa Jallon, Guinea, and had come to Sierra Leone as a young man to "find his own". Unlike many of his former colleagues, he was not a wealthy man and had been unable to take good advantage of Alimamy Jalloh's patronage. He had a small number of cows, perhaps ten or so, which were minded in a nearby warri. Coto Timbi traded mainly with cattle which he bought directly from the warris. His catchment area included Yataia, Yufuni and Kumbakada, which lay between five and seven miles around Kabala. He would occasionally buy cattle from Dogoloya market, but seldom travelled to the larger "international" cattle markets along the Guinea border because cattle prices there were too high. (*14) It was clear that Coto Timbi had close relationships with a number of the warris that he visited. I do not suppose that Coto Timbi had exclusive rights to purchase cattle from these warris but these friends and acquaintances had become regular suppliers and would inform him of cattle they were planning to sell. Whatever, it appeared that Coto Timbi had an established set of trading partners. (*15) Operating on this personal level had obvious drawbacks. The supply of cattle was both erratic and limited. Cattle were normally sold singly, and Coto Timbi considered himself fortunate if he was able to purchase two animals from the same warri, or even from the same "patrol". He sometimes bought smallstock, but traded little in |

|

121 |